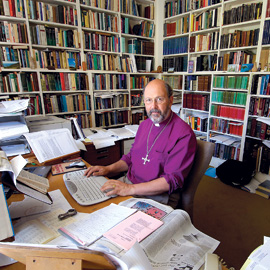

C. S. Lewis Lecture 2011

C. S. Lewis Lecture 2011

'God in the Dock: What Place Now for Christian Faith in Public Life?'

Dublin, Friday October 21 2011

By The Right Reverend Professor N. T. Wright University of St Andrews

It is a privilege and a treat to be back in Dublin once again. And it is an especial privilege to give a lecture associated with the name of that great Irishman, C. S. Lewis.

Even though on some matters - including, I suspect, some at least of what we shall be addressing this evening- I find myself in oblique disagreement with him, I have learnt so much from him that I am bound to offer this presentation as a homage to his memory.

My title tonight, 'God in the Dock', comes - as you may know - from the title of a short essay by Lewis, which was then used as the title of a collection of such works. The pithy pieces that make up this collection are Lewis at his best, arguing a coherent case for the truthof the Christian faith and the reasonableness of belief. The title 'God in the Dock' comes from Lewis's observation that secular modernism, instead of regarding God as the judge before whom we must all stand, has reversed the scenario. God himself is in the dock, with our culture providing prosecution, judge and jury.

What Lewis would have said had he seen today's judges and jurors it is daunting to guess.Lewis imagined his modernist judges to be quite kindly; they were, he says, ready to hear a case for the defence, and might even acquit God of his apparent crimes. Not so the 'New Atheists' of our own day. They stridently accuse God of everything imaginable and allow him no excuses, no defence. Reading people like Richard Dawkins, I am reminded of Kingsley Amis's famous remark when someone asked him if he believed in God. 'No,' he replied, 'and I hate him.' There is a level of raw anger in some of the recent writing which, as many commentators have pointed out, makes the claim to be representing the humanist principle of reason somewhat hard to sustain.

These attacks have brought into sharp public focus certain questions which have been rumbling along in western culture for well over a couple of centuries, and which are nowfacing us - and, so I understand, facing you in Ireland not least - with a new kind of force. Iwant to get at them this evening by putting before you three stories, three narratives, the first two of which are well enough known but the third of which is less so. It won't surprise youthat I am using the usual lecturer's trick of setting up two positions, neither of which I find satisfactory, and offering a third which is not a compromise between them so much as a different kind of story altogether.

1. The Secularist Thesis

You will be as familiar as I am with the mainstream secularist thesis, which has been put before the western world repeatedly over the last two hundred and more years. (I understand that Ireland has quite a different relationship with the Enlightenment to that enjoyed, or endured, by England and indeed Scotland. In fact, my good friend, the Irish American scholar John Dominic Crossan, has frequently remarked that the Irish never really got the Enlightenment, but they got the British instead, which they found most enlightening in other ways.) Nor, for that matter, did Ireland 'get' the Protestant Reformation in the way thatEngland and Scotland did. (I miss out Wales not because it's not important but because I don't know its intellectual history at all.) However, my understanding is that Ireland has been making up for lost time, as it were, in the Enlightenment stakes in recent years. I lived for five years in the Canadian province of Quebec, which I take it offers a partial analogy to theIrish experience. Quebec remained traditionally and vibrantly Roman Catholic while the restof America embraced the Enlightenment. Then, almost overnight in the 1970s, it decided it didn't believe that stuff any more and pursued a vigorous secularisation in all areas of life.The dogged and unquestioning loyalty formerly given to the church was then given instead tothe Parti Quebecois; but that, too, has now been variously discredited and debunked, leaving Quebec puzzled, as the rest of us are, with the ambiguities of modern democracy and economics. You will know better than I the ways in which this process both has and hasn't been mirrored in your own lovely country.

But my point is this: that underneath the slow erosion of the older ways that has taken placein the rest of Europe since the middle of the eighteenth century, and underneath the muchmore rapid erosion that has taken place recently in your country, as in Quebec, there lies a set of beliefs about the world which we can loosely call secular modernism. It tells a consistent story which goes like this. Once upon a time the world was dominated by religion. This caused all kinds of superstition, with people ascribing to supernatural causes phenomena,whether thunderstorms or epilepsy, which are now explained by science. Superstitious religion produced all kinds of wickedness, as the church sought to order and regulate the lives of individuals and whole societies while continuing itself to amass power, wealth and -despite protestations of chastity - to tolerate undercover sexual licence. In fact (so runs the secularist thesis) religion, not least the Christian religion and its Catholic manifestation, has been responsible for many of the major ills in the world, for wars, crusades and inquisitions,repression of women, abuse of children. The church has made people's lives hell in the present in the belief that they were thereby rescuing them from hell in the future.

In fact (concludes the secularist in triumph), we now know that all this is nonsense. Modern science has disproved God, miracles, heaven and hell, the whole lot. Modern history has undermined the old stories about Jesus, particularly his resurrection. Modern politics has shown us that democracy is far better than the old unchallenged divine right of popes and kings. And modern sociology, anthropology and psychology have shown us that human beings are burdened neither with being in the image of 'god' nor with 'original sin'. What they need is education, science, technology and - just now at least - a better economic climate. Then we can all thrive together. Meanwhile the Whig view of history applies to society and morals as to everything else: 'progress' is still under way, things are getting more liberal, more open, more free, and 'now that we live in the twenty-first century' we have to say farewell to all those old superstitions and restrictive moral codes, and welcome the brave new world where 'human rights' means that everyone has the right to do whatever they like.The recent appalling acts of religiously motivated terrorists have only uncovered, declares the secularist, what was there all along: a little religion goes a long way - in entirely the wrong direction.

I caricature only a little. This narrative, or something quite like it, has dominated public discourse in England and Scotland most of my life, getting more strident as it has gone on.Our national media take this for granted as their starting-point. Now, I take it, something similar has become more common in Ireland as well. It is assumed that religion in general and Christianity in particular is out of date, disproved, bad for your health, the cause of many great evils. And it is assumed that the church, as well as peddling this evil thing, is internally corrupt, hypocritical, and unfit for anything except the scrapbook of history. To the question,then, whether Christian faith now has any place in public life, the secularist responds with aresounding 'No'. Voltaire's motto has come home to roost: ecrasez l'infame, 'wipe out the disgrace'. Clear the church and its monstrous teaching off the scene, and we shall build a newkind of new Jerusalem by our own efforts instead. Whenever the church tries to say anythingtoday in the public square, loud voices are raised to tell it to shut up, as I know from my experience in the House of Lords and as you have seen in your own country in the reaction to attempts by the Catholic bishops to oppose the civil partnerships bill. Fortunately, in this first story, the churches are in any case being edged out of the reckoning. They are emptying oftheir own accord, and being sold off for use as homes, wine bars and warehouses. Fairly soon nothing will be left except a nostalgic and increasingly elderly remnant.

2. The Older Story Revived?

My first story, then, is the strident story of contemporary secularism. My second story is, Itake it, a fairly normal Christian response. Most Christians will agree that the church hasmade mistakes. But although some churches are emptying, others are filling, not only in Africa, Latin America and South-East Asia, not only in China, but in our own islands. As a prediction of what would happen, the secularist prophecy has failed. And the intellectual charges of the 'new atheists' have been refuted, point by point, by writers such as Alister McGrath and David Bentley Hart. What's more, several have pointed out that many of the worst crimes against humanity have been committed, not by Christians or indeed Muslims,but by the children of the Enlightenment, the atheistic or even downright pagan Nazis on the one hand and the avowedly atheist Marxists of China and the Soviet Union on the other. The founding heroes of secular modernism, the French Revolutionaries, got rid of the 'disgrace' all right, but they got rid of one another too, at quite an alarming rate. The guillotine and the gas chamber are two of secular modernism's most potent and revealing symbols. As C. S.Lewis himself pointed out, if this is 'progress', it is the kind of 'progress' you see in an egg: 'We call it "going bad" in Narnia,' declares Prince Caspian.

What's more, reply the traditionalists quite rightly, one needs to distinguish good religion from bad. Christians, Muslims and Jews, after all, got on more or less all right as neighboursin the middle East for hundreds of years. The strident terrorism of recent decades is almost entirely a 'modern' phenomenon, even in some senses a postmodern one.

But the story which the Christian respondents have been telling has, by and large, not really addressed - so far as I am aware - the deeper question of whether there is therefore any placefor Christian faith in public life. Nor has it addressed, I think, the question which is urgent in Ireland right now, the question of how on earth the church not only perpetrated such massive and horrible abuse but has then done its best to cover it up. I am not sure that those who want to tell the second story have really come to grips with sheer cold fury expressed by your Prime Minister a couple of months ago on behalf of millions of ordinary people. Perhaps that is why a good deal of the response to the first story has simply concentrated on rebutting the charge that Christianity is disproved or bad for you, leaving the Christianity thus defended as basically a private faith, which the church can then proclaim, and people can believe, with integrity and good reason. Much of the defence has assumed, it seems to me, that when we have seen off the newer challenges we can resume business as normal - a bit like the banks after the credit crunch. And I hold the view that what was 'normal' for the Christian churches in the western world after the Enlightenment is not in fact 'normal' by the canons of classic Christianity. We need to revisit the larger, underlying questions, and not assume that the way we were functioning before was basically all right once we'd cleaned up a few small details.That, in fact, as you will know better than I, is how the church has often been perceived:covering up mistakes or imagining that they can be parked to one side, allowing the main business to proceed without noticing serious cracks in the structure. The twin dangers of nostalgia and complacency are always with us. However effective the church's answers to the new atheists, this does not absolve us from thinking afresh, first about just how the church allowed itself to get into the mess in the first place, and second, only then, about how a healthy Christian faith and life might impinge upon public life in our world and our day.

I'm not sure I'm competent to deal with the first question, important though it is. My hunch isthat the church has, over many generations, allowed itself simultaneously to do two things.First, it has colluded with the Enlightenment proposal that Christianity is simply about 'religion' and 'morality' - but since 'morality' has been such a contested area, and since inany case one can always repent, a slow decline in actual moral standards has taken place,accelerated by the liberalism of the 1960s. Second, in many churches, not least but not only the Roman church, ordination or its equivalent has been supposed to put people on a new kind of level altogether, so that people find it hard to believe ill of them and so that theythemselves, and their superiors, tend to assume that any moral failures are an odd blip rather than a major character defect. All churches, and all clergy, need to look hard in the mirror at this point.

Only then, with genuine penitence, can we address the possibility of Christian faith andpublic life. Here I will inevitably speak against the tide. To an outsider it looks as though Ireland is at last plugging into the anti-Christian, anti-Catholic and anti-clerical reaction which Voltaire articulated and which has dominated much of the rest of Europe, not to mention America. Scandals in the church on the one hand, and the ostensible 'religious' alignments in 'the troubles' to the north, make all this much worse, but I don't think that is the underlying problem.

Whether or not I am right about that, it is time to move to my third narrative. I want to propose a way of looking at the role of Christian faith in public life which is not well known.Even to articulate it requires us to step back a bit and consider two things: what Jesus and his first followers were actually saying, and what has happened to western culture - and now finally, it seems, to Ireland where Christian western culture began in the first place! - in the last few generations.

3. The Kingdom of God and the Kingdoms of the World

The third story I wish to tell must begin with Jesus himself. Interestingly, the new atheiststend to assume that Jesus can be safely discounted as a minor figure whose followers, afterhis death, invented a few stories about him and a religion around him. Christian apologists,myself included, have responded by saying that actually the stories in the gospels are farmore historically reliable than you might think. But we have not usually gone beyond this to a fresh articulation of what was, arguably, central for Jesus: the notion of the kingdom ofGod.

Here we face a new kind of puzzle. For many Christians it would have been sufficient if Jesus of Nazareth had been born of a virgin and died on a cross, and never done anything much in between. Insofar as the gospels record his deeds and words, these simply function to teach doctrines and ethics we might have learnt from Paul or elsewhere. But this characteristic western misreading of the gospels omits the central point: that Jesus went about announcing that God was now in charge, doing things which embodied that in-charge-ness, that sovereignty, that 'kingdom', and telling stories which explained that this divine kingdom wascoming, not in the way people were expecting, but like a tiny seed producing a huge shrub,like a father welcoming back a runaway son. All the gospels record that Jesus' public career began with an incident which marked him out as the long-awaited king of Israel; they all record that he died with the words 'king of the Jews' above his head. In the biblical tradition,the expected king of the Jews is the king of the world, the one through whom the creator Godwill establish his rule across the whole world. That claim is made explicit at the end of Matthew's gospel: all authority, says the risen Jesus, is given to me in heaven and on earth.Most western Christians have been happy to suppose that Jesus now has authority in heaven (whatever that means); few have even begun to contemplate what it might look like for himto have authority on earth as well.

There are two obvious reasons why this extraordinary claim is usually not even noticed. Both relate directly to the challenge of 'doing God in public', of Christian faith and public life.First, it is unbelievable; second, it is undesirable. First, people in Jesus' own day and ever since have responded to Jesus' own claims and those of his followers by saying that it'sobvious the kingdom of God has not arrived. Look out of the window, they say. Read the newspapers. If God was in charge, why is the world still in such a mess? (Of course, Jesus' followers knew this too, but they went on making the claim.) Second, western culture has struggled over many centuries to throw off what it sees precisely as theocracy, recognisingthat when people claim that God's in charge what they normally mean is that their interpretation of God and his rule must be given absolute status. The rule of God quickly becomes the rule of the clerics. Today's fundamentalist terrorism has sharpened up our reaction to this idea, but this reaction itself goes back not only to the Enlightenment, not only to the uneasy settlements of the Reformation, but as far back as the Renaissance itself. It is possible, in fact, to represent the history of western politics as the history of the gradual diminishment of 'theocracy' and its displacement by . . . by what?

Well, there's the problem. There have been two great movements of thought and life in the last two hundred years. Both have had direct results on the church and its place in public life.Most obviously, there have been the movements of revolution, from France in the 1770s to China and Russia in the mid-twentieth century. In these movements, crucially, the State is divinized; it becomes the highest good, the supreme value, the ultimate giver of meaning andlife. The State in question must therefore be de jure atheist, not simply because people happen not to believe in God but because there is no room for God in the structure. Those who persist in believing in God are therefore classified as mad, deranged, a danger to society; there can be no place for the church in public life, and indeed ideally no place for the church at all. The failure of the great revolutionary systems to destroy the church, and the way in which, when Eastern European communism fell, some of the movements of opposition were explicitly Christian, has reduced today's hard Left in Europe to head-shaking and head-scratching, but has not produced major new insight.

But, second, there have been the great liberal democracies of the western world, now ironically regarded by many other countries as the kind of system they wish to aspire to at thevery point when they, the democracies, are showing signs of wear and tear. And the point that has been made with increasing clarity about them is that, though they haven't tried to replace God, they have tried to replace the church. In my own country, this is happening most obviously in David Cameron's idea of the 'Big Society', where everyone is supposed to be involved in making things happen in their local communities, in caring for the needy. This was, historically, what the church at its best always did, founding hospitals and schools andso on, and, recently, launching the hugely successful hospice movement and campaigning for remission of global debt. But the church in the west has by and large colluded with this displacement, and has been content to occupy the new, diminished role marked out for it by the philosophy of the Enlightenment, the role of providing a space for 'religion', somewhere quiet on the side. This is where today's debate about Christian faith in public life must learn to engage.

The Enlightenment, in its various waves, saw itself as finally implementing the Epicureanagenda first glimpsed with the rediscovery of Lucretius early in the fifteenth century, a findevery bit as momentous as Martin Luther's rediscovery of St Paul early in the sixteenth. The point about Lucretius (who lived about a hundred years before Jesus) and his Epicureanism was that its foundational idea was the banishing of the gods to a far-away heaven, leaving theworld and mortals to get on with their happy business, uninterrupted and unimpeded, here below. This became the explicit foundation of the modernist agenda to overthrow superstition and religious authority. Indeed, it was Lucretius's account of the development of civilization and of the 'social contract' that, through thinkers like Hobbes and Rousseau, 'enabled historians and philosophers to free themselves from theist models of the foundations of human society' (Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd edn revised, 890). Thus, though thinkers inthis tradition today like to suggest that their views are the result of modern science, a more profound analysis would reveal that modernist science itself, and also the movement for liberal democracy, have simply presupposed the Epicurean worldview. The gods are gone,and the world of nature on the one hand and the world of human society on the other must evolve under their own steam. This then generates a matching split: as between the gods andthe world, so between church and society. The church must get on with God's business,which is redefined as inculcating spirituality in the present and a far-off heavenly salvation in the future, for those who want or believe in such things. But the church, by definition within the dominant Epicurean worldview, has no place in society or public life. The overthrow of the old mediaeval order in the Renaissance, and of the old Catholic order in the Reformation,became the overthrow of the whole Christian order in the Enlightenment. What I believe you are seeing in Ireland today is what, in a less crisp and more muddled fashion, we have seen in England and Scotland in bits and pieces over many years, namely the sharp and brittle clarity gained from the simple disjunction of heaven and earth, of God's world and our world. This disjunction was not itself the result of, but rather the presupposition for, these great movements of western thought and life. Charles Darwin didn't invent Darwinism. Lucretius had argued it, elegantly, two thousand years earlier. Biological evolution is one thing; but the idea that there is no creator God involved in this process is something quite different.

The church, however, has been happy to go along with the disjunction of God's world and ours. The seeds of this were planted, I think, in the Middle Ages themselves, through the heavy over-concentration on the afterlife, on Dante's vision of heaven, hell and especially purgatory, and on the vision of the End so brilliantly displayed in Michaelangelo's Sistine Chapel. 'This world is not my home,' sang the African-American spiritual, 'I'm just a passing through'; but those sentiments merely popularized a vision of 'what really mattered' which had been around for many centuries. And so it was not only the thinkers of the Enlightenment, eager to get on with carving up the world the way they wanted and therefore keen on not having the church telling it what it could and couldn't do, who told the church it should concentrate on God, the soul and heaven. It was many in the church itself. That's partly why William Wilberforce had such a hard time in pushing his agenda of freeing the slaves, why Desmond Tutu faced an uphill struggle in South Africa, and why today Christian activists face such problems in campaigning for the dropping of massive international debt, or the proper and humane treatment of asylum seekers. It isn't just that vested financial and political interests have been ranged on the other side. It is that the entire climate of thought is against the church having anything to say on such subjects at all. God and Caesar belong in entirely separate compartments. That is why France is now banning Muslim headdress for women. It is why some have tried to ban the wearing of crosses in public, and why some councils in my country have, ridiculously, replaced Christmas celebrations with 'Winterval' and the like. The excuse for reducing Christian content is always that religious minorities might be offended. But that's not the real reason, as the French ban indicates. 'Tolerance', that much-vaunted but actually very hollow Enlightenment ideal, has nothing to do with it.The real reason is the modernist ideology according to which religion is something for consenting adults in private, because God and the world simply don't mix. And that, to repeat, is not the result of modern physical or political science. It is its presupposition.

What then might the church have to say to all this? The western church has by and large given up the idea of the kingdom of God, of God claiming his rightful sovereignty over the whole of creation. Generations have been schooled to read Jesus' language about the kingdom as referring, not to God's saving rule over creation, but to a heavenly kingdom into which God will receive those he has rescued from creation. Jesus' saying to Pontius Pilate is often quoted, 'My kingdom is not of this world'; but what Jesus actually said was 'My kingdom is not from this world,' ek tou kosmou toutou (John 18.36). The crucifixion scene makes it quite clear that, though Jesus' sovereignty comes from somewhere else, it is intended for this world. And when Christians protest, as they sometimes do, about the banning of Christian symbols from the public sphere, they tend to argue from within the consensus rather than taking the harder route of understanding why the consensus is there in the first place and why and how it must be challenged. That is the problem, I think, with the current reaction to the 'new atheists'. The reaction, or much of it, has happened within the implicit structure of thought. But it's the structure that must be challenged.

But the challenge must come, not in the name of the kind of 'theocracy' of which the westernworld is so understandably afraid, but in the name of the utterly redefined and reshaped theocracy of which the four gospels speak. The crucifixion scene, in which Jesus is lifted up as king of the Jews and hence king of the world, is also the scene through which power itself is redefined. And it is in that redefinition of power that we may glimpse, as though for the first time, the vital, crucial and God-given place which the church, and Christian faith, can and must have in tomorrow's public life.

It isn't a matter, you see, of the church claiming a small slice of the ordinary kind of power.Actually, even in my country where some bishops sit in the House of Lords, this isn't amatter of power, though that was clearly the case at one time. The way it works today is to ensure that the voice of the churches is heard at the table. But that's not the point; that's not, in any case, the kind of power which should concern a theocracy remoulded around the cross of Jesus.

Jesus' kind of power looks completely different - not because it's 'spiritual' as opposed to 'worldly' or 'earthly' (that's the route to Gnosticism) but because it operates as a direct result of Jesus' own agenda and the cross with which that agenda reached its triumphant, if deeply paradoxical, conclusion.Jesus' kind of power was set out, famously, in the Sermon on the Mount. But the Sermon too has often been misunderstood. When Jesus announces, in the Beatitudes, his blessing on certain kinds of people, we should remember what 'blessing' actually means. The 'Beatitudes' are Jesus' agenda for kingdom-people. They are not simply about how to behave so that God will do something nice to you. They are about the fact that Jesus wants to rule theworld through you, but that for that to happen you'll have to become people of this kind. TheSermon on the Mount is a call to Jesus' followers to take up their vocation, which was the Israel-vocation that Jesus made his own: the vocation to be light to the world, to be salt to theearth - in other words, to be people through whom Jesus' kingdom-vision was to become areality. The victory of Jesus over the powers of sin and death is to be implemented in the wider world through people like this.

The work of the kingdom, in fact, and with it the place of Jesus' followers in the public life ofthe world, is summed up pretty well in those Beatitudes. When God wants to change the world, he doesn't send in the tanks. He sends in the meek - the mourners, those who are hungry and thirsty for God's justice, the peacemakers, and so on. Just as God's whole style,his chosen way of operating, reflects his generous love, sharing his rule with his human creatures, so the way in which those humans then have to behave if they are to be agents ofJesus' Lordship reflects in its turn the same sense of vulnerable, gentle but powerful self giving love. It is because of this that the world has been changed by people like William Wilberforce; by Desmond Tutu, working and praying not just to end Apartheid but to end itin such a way as to produce a reconciled, forgiving South Africa; by Cicely Saunders, starting a Hospice for terminally ill patients, initially ignored or scorned by the medical profession,but launching a movement that has, within a generation, spread right round the globe.

Jesus rules the world today by launching new initiatives that radically challenge the acceptedways of doing things: by Jubilee projects to remit ridiculous and unpayable debt, by housing trusts that provide accommodation for low-income families or homeless people, by local and sustainable agricultural projects that care for creation instead of destroying it in the hope of quick profit. And so on. We have domesticated the Christian idea of 'good works' so that it has simply become 'the keeping of ethical commands' - so that then people imagine that the place of Christian faith in public life will be a matter of imposing 'our standards' on everyone else. Instead, in the New Testament, 'good works' are what Christians are supposed to be doing in and for the wider community. Do good to all people, insists Paul, especially (ofcourse) your fellow-Christians (Galatians 6.10). That is how the sovereignty of Jesus is put into effect. Jesus went about feeding the hungry, curing the sick and rescuing lost sheep; his Body is supposed to be doing the same. That is how his kingdom is at work. The church, in fact, made its way in the world for many centuries by doing all this kind of thing. Now that in many countries the 'state' has assumed responsibility for many of them (that's part of what Imean by saying that the state, not least in western democracies, has become 'ecclesial', a kind of secular shadow-church) the church has been in danger of forgetting that these are its primary tasks.

This vision of the church's calling - to be the means through which Jesus continues to workand to teach, to establish his sovereign rule on earth as in heaven - is an ideal so high that it might seem not only unattainable and triumphalistic but hopelessly out of touch and in denial about its own sins and shortcomings. One of today's most-repeated clichés is that there arelots of people who find God believable but the church unbearable, Jesus appealing but thechurch appalling. We are never short of ecclesial follies and failings, as the sorrowing faithful and the salivating journalists know well. What does it mean to say that Jesus is King when the people who are supposed to be putting his kingship into practice are letting the side down so badly?

There are three things to say here, and each of them matter quite a lot. To begin with, forevery Christian leader who ends up in court or in the newspapers there are hundreds and thousands who are doing a great job, unnoticed except within their own communities. The public only notices what gets into the papers, but the papers only report the odd and the scandalous, allowing sneering outsiders to assume that the church is collapsing into a little heap of squabbling factions. Mostly it isn't. The newspaper-perspective is like someone who only walks down a certain street on the one day a week when people put out their garbage for collection, and who then reports that the street is always full of garbage. Christians ought not to collude with the sneerers. Walk down the street some other time, we ought to say. Come and see us on a normal day.

Second, though, we must never forget that the way Jesus worked then and works now is through forgiveness and restoration. The church is not supposed to be a society of perfect people doing great work. It's a society of forgiven sinners repaying their own unpayable debt of love by working for Jesus' kingdom in every way they can, knowing themselves to be unworthy of the task. I suspect that part at least of the cause of the scandals is, as I suggested before, the triumphalism which allows some people to think that because of their baptism, orvocation, or ordination, or whatever, they are immune to serious sin - or that, if it happens, it must be an odd accident rather than a tell-tale sign of a serious problem.

But the third point is perhaps the most important, and it opens up a whole new area at which I glanced earlier on and to which we now return. The way in which Jesus exercises his sovereign lordship in the present time includes his strange, often secret, sovereignty over the nations and their rulers. God, insists the Bible, is at work in all sorts of ways in the world,whether or not people acknowledge him. But part of this belief is the belief that one of thechurch's primary roles is to bear witness to the sovereign rule of Jesus, holding the world to account. The church has atask which modern western democracies have attempted to replicate in other ways. We have tried to produce, within our systems, some semblance of 'accountability'. If the voters don't like someone, they don't have to vote for them next time. We all know that this is a very blunt instrument. Accountability isn't all it's cracked up to be. In my country, most of the seats are 'safe', and most of the candidates are professional party hacks with little experienceof real outside life.

So those who follow Jesus have the task, front and centre within their vocation, of being the real 'opposition'. This doesn't mean that they must actually 'oppose' everything that the government tries to do. They must weigh it, sift it, hold it to account, affirm what can be affirmed, point out things that are lacking or not quite in focus, critique what needs critiquing,and denounce, on occasion, what needs denouncing. It is telling that, in the early centuries of church history, the Christian bishops gained a reputation in the wider world for being the champions of the poor. They spoke up for their rights; they spoke out against those who would abuse and ill-treat them. Of course: the bishops were followers of Jesus; they sang his mother's song; what else would you expect? That role continues to this day. And it goes much wider. The church has a wealth of experience, and centuries of careful reflection, in the fields of education, health care, the treatment of the elderly, the needs and vulnerabilities of refugees and migrants, and so on. We should draw on this experience and use it to full effect.

This facet of the church's 'witness', this central vocation through which Jesus continues hiswork to this day, has been marginalized. Modern western democracies haven't wanted to beheld to account in this way, and so have either officially or unofficially driven a fat wedge between 'church' and 'state'. (The newspapers have joined in, as the self-appointed 'unofficial opposition'; they, too, have therefore a vested interest in keeping the church of fthe park.) But, as we have hinted already, this has actually changed the meanings of the words 'church' and 'state'. 'State' has expanded to do some of what 'church' should bedoing; and the churches themselves have colluded with the privatization of 'religion', leaving all the things that the church used to be best at to 'the state' or other agencies. No wonder,when people within the church speak up or speak out on key issues of the day, those who don't like what they say tell them to go back to their private 'religious' world. (Have you noticed, incidentally, that in America it's usually the left who tell the church to shut up, and in the UK it's usually the right? I'd be interested to know what it is here in Ireland.) But speak up, and speak out, we must, because we have not only the clear instruction of Jesus himself but the clear promise that this is how he will exercise his sovereignty; this is how he will make his kingdom a reality. In John's gospel Jesus tells his followers that the Spirit will call the world to account. This is central to Christian vocation, but for most it remains aclosed book. Of course, the church will sometimes get it wrong. If the church is to exercise a prophetic gift towards the world, this will require further prophetic ministries within the church itself, to challenge, confront and correct, as well as to endorse, what has been said.

This, then, is a central and often ignored part of the meaning of Jesus' kingdom for today.Each generation, and each local church, needs to pray for its civic leaders. Granted the wide variety of forms of government, types of constitution and so forth that obtain across the world, each generation, and each local church, needs to figure out wise and appropriate ways of speaking the truth to power. That is a central part of the present-day meaning of Jesus' universal Kingship.

We can sum it all up like this. We live in the period of Jesus' sovereign rule over the world -a reign that is not yet complete, since as Paul says 'he must reign until he has put all hisenemies under his feet', including death itself (1 Corinthians 15.20-28). But Paul is clear: we do not have to wait until the second coming to say that Jesus is already reigning. In trying tounderstand this present 'reign' of Jesus, though, we have seen two apparently quite different strands. On the one hand, we have seen that all the powers and authorities in the universe arenow, in some sense or other, subject to Jesus. This doesn't mean that they all do what he wants all the time; only that Jesus intends that there should be social and political structures of governance, and that he will hold them to account. We should not be shy about recognising- however paradoxical it seems to our black-and-white minds! - the God-givenness of structures of authority, even when they are tyrannous and violent and need radical reformation. We in the modern west have trained ourselves to think of political legitimacy simply in terms of the method or mode of appointment: once people have voted, that confers 'legitimacy'. The ancient Jews and early Christians, though, were not particularly interested in how rulers had come to be rulers. They were far more interested in holding rulers responsible in terms of what they were actually doing once in power. God wants rulers; but God will call them to account.

Where does Jesus come into all this? From his own perspective, he was both upstaging the power structures of his day and also calling them to account, right then and there. But his death, resurrection and ascension were the demonstration that he was Lord and the powers and authorities were not. The calling-to-account has, in other words, already begun. It will be completed at the second coming. And the church's work of speaking the truth to power means what it means because it is based on the first of these and anticipates the second. What the church does, in the power of the Spirit, is rooted in the achievement of Jesus and looks ahead to the final completion of his work. This is how Jesus is running the world in the present.

But, happily, it doesn't stop there. There is more to the church's vocation than the constant critique, both positive and negative, of what the world's rulers are getting up to. There are millions of things which the church should be getting stuck into that the rulers of the world either don't bother about or don't have the resources or the political will to support. Jesus hasall kinds of projects up his sleeve and is simply waiting for faithful people to say their prayers, to read the signs of the times, and to get busy. Nobody would have dreamed of a' Truth and Reconciliation Commission' if Desmond Tutu hadn't prayed and pushed and made it happen. Nobody would have worked out the Jubilee movement, to campaign for international debt relief, if people in the churches had not become serious about the ridiculous plight of the poor. Closer to home, nobody else is likely to volunteer to play the piano for the service at the local prison. Few other people will start a play-group for the children of single mothers who are still at work when school finishes. Nobody else, in my experience, will listen to the plight of isolated rural communities or equally isolated inner-city enclaves.Nobody else thought of organising the 'Street Pastors' scheme which, in my country at least,has had a remarkable success in reducing crime and gently but firmly pointing out to aimless young people that there is a different way to be human. And so on. And so on.

And if the response is that these things are all very small and, in themselves, insignificant, Ireply in two ways. First, didn't Jesus explain his own actions by talking about the smallest ofthe seeds that then grows into the largest kind of shrub? And second, haven't we noticed how one small action can start a trend? That's how the Hospice movement spread, transforming within a generation the care of terminally ill patients. Jesus is at work, taking forward his kingdom-project.

He is, no doubt, doing this in a million ways of which we see little. The cosmic vision ofColossians is true, and should give us hope, not least when we have to stand before local government officials and explain what we were doing praying for people on the street, or why we need to rent a public hall for a series of meetings, or why we remain implacably opposed to a new business that is seeking shamelessly to exploit young people or low-income families. When we explain ourselves, we do so before people who, whether or not they know it, have been appointed to their jobs by God himself. Jesus has, on the cross, defeated the power that they might have over us. And, as we pray, and proclaim Jesus' death in the sacraments, we claim that victory and go to our work calmly and without fear.This is, after all, what Jesus himself told us to expect. The poor in spirit will be making the kingdom of heaven happen. The meek will be taking over the earth, so gently that the powerful won't notice until it's too late. The peacemakers will be putting the arms manufacturers out of business. Those who are hungry and thirsty for God's justice will be analysing government policy and legal rulings and speaking up on behalf of those at the bottom of the pile. The merciful will be surprising everybody by showing that there is a different way to do human relations: some people know only how to be judgmental, to give as good as they get, to lash out and get their own back, but the Beatitude-people will unveil, and by their example encourage, a refreshingly different way. You are the light of the world,said Jesus. You are the salt of the earth. He was announcing a programme yet to becompleted. He was inviting his hearers, then and now, to join him in making it happen.

This is what it looks like when Christian faith is doing its job within the public life of today's andtomorrow's world. My hope and prayer is that you in your country and I in mine will be able to work through the present troubles, sorrows and scandals. Ireland was once the teacher ofthe world in matters of faith and life. May it be so again.