We say it before meals. We give our daughters the name. We use the word in endless book titles. Yes, I'm talking grace.

We say it before meals. We give our daughters the name. We use the word in endless book titles. Yes, I'm talking grace.

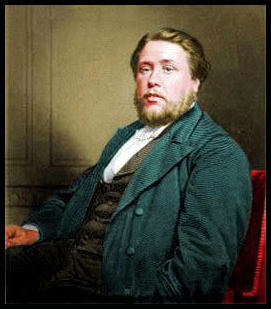

So what does grace actually mean, and how should it revolutionize my ordinary life? In his new book, One-Way Love: Inexhaustible Grace for an Exhausted World (David C. Cook), Tullian Tchividjian sets out to explore and revel in the untamable, unstoppable reality of God's invading grace.

I talked with Tchividjian, pastor of Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, about the urgency of his message, common misunderstandings, motivations versus reasons, "holy sweat," and more.

********

Why do you think the news of God's inexhaustible grace for an exhausted world has "never been more urgent"?

There's a quotation that astonishes me every time I see it: Dr. Richard Leahy, a prominent psychologist and anxiety specialist, said a couple of years ago that "the average high school kid today has the same level of anxiety as the average psychiatric patient in the early 1950s." Wow. There's also a statistic The New York Times reported in 2007, showing that 30 percent of American women admit to taking sleeping pills before bed most nights. And that's just the ones who admit it!

tullian

The news of God's inexhaustible grace has never been more urgent because the world has never been more exhausted. In our culture where success equals life and failure equals death, people spend their lives trying to secure their own meaning, worth, and significance. And as a result our culture is exhausted emotionally, physically, relationally, spiritually. Real life is long on law and short on grace—the demands never stop, the failures pile up, and fears set in. Life requires many things from us—a successful career, a stable marriage, well-behaved and emotionally adjusted children, a good reputation, and a certain quality of life. We do our best to do better, do more, and do now. We live with long lists of things to accomplish, people to please, and situations to manage. Anyone living inside the stress, strain, and uncertainty of daily life knows from instinct, and hard experience, that the weight of life is heavy. We all need some relief.

But there's another reason, too: God's inexhaustible grace needs to be announced ever more urgently because the church, God's chosen mouthpiece in the world, has been so neglectful in announcing it! So many churches, either accidentally or purposefully, encourage our innate performancism—giving us nine ways to be better dads or seven ways to be more faithful stewards—that the landscape is littered with ex-church members. The percentage of Americans claiming no religious affiliation, which was 7 percent in 1990, had shot up to 16 percent by 2010.

In recent years, a handful of books have been published urging a more robust, radical, and sacrificial expression of the Christian faith. I even wrote one of them—Unfashionable: Making a Difference in the World by Being Different. I heartily "amen" the desire to take faith seriously and demonstrate before the watching world a willingness sacrificially serve our neighbors rather than ourselves. The unintended consequence of this push, however, is that if we're not careful we can give the impression that Christianity is first and foremost about the sacrifice we make for Jesus rather than the sacrifice Jesus made for us; our performance for him rather than his performance for us; our obedience for him rather than his obedience for us. The hub of Christianity is not "do something for Jesus"; it's "Jesus has done everything for you." I fear too many people, both inside and outside the church, have heard this plea for intensified devotion and concluded the foundation of the Christian faith is our love for God instead of God's love for us.

In what ways is grace most commonly misunderstood today?

I think the main way is when people confuse it with cheapened law. Think of the first and greatest commandment: "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind" (Matt. 22:37). Or think of Jesus' crushing line in the Sermon on the Mount: "You therefore must be perfect, as your Father in heaven is perfect" (Matt. 5:48). Grace, for many Christians, is the reduction of God's expectations of us. Because of grace, we think, we just need to try hard. Grace becomes this law-cheapening agent, attempting to make the law easier to follow. "Love the Lord with all your heart" becomes "try to love God more than sports." "Be perfect" gets cheapened into "do your best."

J. Gresham Machen counterintutively noted, "A low view of law always produces legalism; a high view of law makes a person a seeker after grace." The reason this seems so counterintuitive is because most people think those who talk a lot about grace have a low view of God's law (hence, the regular charge of antinomianism). Others think those with a high view of the law are the legalists. But Machen makes the compelling point that it's a low view of the law that produces legalism, since a low view of the law causes us to conclude we can do it—the bar is low enough for us to jump over. A low view of the law makes us think the standards are attainable, the goals reachable, the demands doable. This means, contrary to what some Christians would have you believe, the biggest problem facing the church today is not "cheap grace" but "cheap law"—the idea that God accepts anything less than the perfect righteousness of Jesus. As essayist John Dink writes,

Cheap law weakens God's demand for perfection, and in doing so, breathes life into the old creature and his quest for a righteousness of his own making. . . . Cheap law tells us that we've fallen, but there's good news, you can get back up again. . . . Therein lies the great heresy of cheap law: it is a false gospel. And it cheapens—no—it nullifies grace.

Only when we see that the way of God's law is absolutely inflexible will we see that God's grace is absolutely indispensable. A high view of the law reminds us that God accepts us on the basis of Christ's perfection, not our progress. Grace, properly understood, is the movement of a holy God toward an unholy people. He doesn't cheapen the law or ease its requirements. He fulfills them in his Son, who then gives his righteousness to us. That's the gospel. Pure and simple.

What's the role of grace-motivated effort—what the Puritans called "holy sweat"—in the Christian life?

In Galatians 5:6 Paul makes a stunning statement: "For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision has any value. The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love." And then in Romans 10:17 he makes the point that "faith comes through hearing the word about Christ."

According to Paul, real love is impossible without faith. Faith is upward—it's trusting that everything I need and long for, I already have because of what Jesus has accomplished for me. Love, on the other hand, is outward—because Jesus has done everything for me (faith) I can now do everything for you (love) without needing you to do anything for me. That's not to say love isn't also vertical—it is. We love God, not just others (more on this in the next answer). But the good works we're called to are always directionally horizontal. See the book of James. The implication of Paul's words is that love is absent to the degree that faith is missing. If I'm not trusting that everything I need in Christ I already possess (lack of faith), then I will be looking to take from you rather than give to you (lack of love). I'll be concentrating on what I need, not what you need. I'll be looking out for me, not you.

So if we ever hope to "love our neighbor as ourselves" (which is precisely what God's law calls for), it will depend on faith. And faith, according to Romans 10:17, depends on hearing the gospel—over and over and over again. God stokes faith through the preaching of the gospel, and since our faith needs constant stoking, the preaching of the gospel needs to be constant. As long as love is needed (which is always), faith must be fueled. And the only fuel for faith is the gospel. The logical formula, then, goes like this:

No faith = no love

No gospel = no faith

Therefore, no gospel = no love.

The preaching of the gospel alone activates faith, and faith alone activates love.

So, with Paul, I'm all for faith-fueled, grace-motivated effort, as long as we understand it's not our efforts, but God's effort for us in Christ, that has fully and finally set things right between God and sinners. The Reformation was launched by (and contained in) the idea that it's not doing good works that makes us right with God. Rather, it's the one to whom righteousness has been given who will do good works—that is, sacrificially love and serve our neighbor. Any talk of sanctification, therefore, which gives the impression that our efforts secure more of God's love, itself needs to be mortified. As Scott Clark has said, "We cannot use the doctrine of sanctification to renegotiate our acceptance with God." We fight sin ("holy sweat"), in other words, not because our sin blocks God's love for us (Rom. 8:31ff.), but because our sin blocks our love for God and others. We must always remind Christians that the good works that necessarily flow from faith are not part of a transaction with God—they are for others. After all, God doesn't need our good works, but our neighbor does.

The Christian life is not "let go and let God" but "trust God and get going"—trust that, in Christ, God has settled all accounts between him and you and then "get going" in sacrificial service to your wife, your husband, your children, your friends, your enemies, your co-workers, your city, the world. The vertical declaration that everything we need we already possess in Christ forever secures us and therefore frees us to see the needs around us and work hard horizontally ("holy sweat") to meet those needs.

How do we balance the glorious reality of one-way love with the "greatest commandment" to love God back?

Well, the greatest commandment is not really a command to love God "back"; it's a command to love him period—to love him in the first place! I think we should be really careful with the word "balance," because I think it's easily misunderstood. The law (of which the greatest commandment is a prime example) and the gospel ("the glorious reality of one-way love") aren't "balanced." One shows us our need, the other announces our provision. We're in constant need of hearing both. It's not 50/50. It's 100 percent law followed by 100 percent gospel. As Gerhard Ebeling wrote, "The failure to distinguish the law and the gospel always means the abandonment of the gospel." What he meant was that a confusion of law and gospel (trying to "balance" them) is the main contributor to moralism in the church because the law gets softened into "helpful tips for practical living" instead of God's unwavering demand for absolute perfection, while the gospel gets hardened into a set of moral and social demands we "must live out" instead of God's unconditional declaration that "God justifies the ungodly." As my friend and New Testament scholar Jono Linebaugh,says, "God doesn't serve mixed drinks. The divine cocktail is not law mixed with gospel. God serves two separate shots: law then gospel."

The greatest commandment—to love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength—casts an incredibly bright light on our failure to love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength. In fact, it's commandments like this that make one-way love so necessary. We're incapable of loving God in the way he deserves, and so find ourselves in desperate need of a Savior. Before God's holy law, we are judged and rightly found wanting. I'm not the follower of Christ I ought to be, nor am I the father, husband, pastor, or friend I should be. I wish I could say I do everything for God's glory. I can't. Neither can you. What I can say is that Jesus' blood covers all my efforts to glorify myself. I wish I could say Jesus fully satisfies me. I can't. Neither can you. What I can say is Jesus fully satisfied God for me.

Paradoxically, it's the glorious fact of one-way love that subsequently enables and empowers us to love God—imperfectly, but nevertheless, really. "We love," as we well know, "because he first loved us." (Incidentally, love for God doesn't happen simply because he commands us to love him—we love God because he first loved us. Love, and love alone, begets love.) So the greatest commandment and one-way love are related, but it's not as simple as being balanced. The command shows us our sin and drives us to cry out for a Savior. God, through this Savior, so overwhelms us with his one-way love (love for the unlovable and undeserving) that we're inspired to love God and others. Charles Spurgeon nailed it when he remarked, "When I thought God was hard, I found it easy to sin; but when I found God so kind, so good, so overflowing with compassion, I beat my breast to think I could ever have rebelled against One who loved me so and sought my good."

The Bible includes exhortations that appeal to a wide range of motivations. As a pastor, how do you determine when it's time to counsel someone not only to "run to the cross," but also to "run away from sin" or to "run for the crown"?

I want to push back a little on this one, or at least challenge the choice of words. I think the Bible includes exhortations that appeal to a wide range of "reasons," but I'd like to suggest "reasons" are very different from "motivations." For instance, we might say that a reason to follow the law is to simply please God. After all, Hebrews talks about our good deeds being pleasing to God (perhaps we could call this "running for the crown"). But there's a distinct difference between a reason to be obedient and a motivation that actually produces obedience. It's all well and good to say there are many reasons to obey, but what actually motivates you to be obedient? The idea that we act based on reasons—we act to please God because it's "the right thing to do"—presupposes that we act rationally. But that's the very idea that the Reformers rejected! Just because we have a reason to be good doesn't mean we'll do it—we have to want to. As John Piper says, we always choose according to what we desire most. We need more than reasons, then—we need motivation.

A lot of preaching these days is too theoretical and disconnected from reality when it comes to the human condition and how real change happens. We use language like "indicatives" and "imperatives." We love phrases like "faith alone saves but the faith that saves is never alone" and "grace is opposed to earning, not effort." And all of those categories and phrases are good. I affirm them all theologically. But none of them answers this question: how does change actually happen?

When it comes to real heart change, we have two options: law or grace. That's it. Two. At the end of the day we either believe law changes or love does. I can tell people all day long about what they need to be doing and the ways they're falling short (and that's important to keep them seeing their need for Jesus). But simply telling people what they need to do doesn't have the power to make them want to do it. I can appeal to a thousand different biblical reasons why someone should start doing what God wants and stop doing what he doesn't want—heaven, hell, consequences, blessing, and so on. And I do. But simply telling people they need to change can't change them; giving people reasons to do the right and avoid the wrong, doesn't do it. Both are necessary, but neither can actually change the person.

Paul makes it clear in Romans 7 that the law endorses the need for change but is powerless to enact change—that's not part of its job description. It points to righteousness but can't produce it. It shows us what godliness is, but it cannot make us godly. The law can inform us of our sin but it cannot transform the sinner. The law can instruct, but only grace can inspire. Or to put it another way, love inspires what the law demands.

Think about it: beneath your happiest moments and closest relationships inevitably lies some instance of being loved in weakness or deserved judgment. Someone let you off hook when you least deserved it. A friend suspended judgment at a key moment. Your father was lenient when you wrecked his car. Your teacher gave you an extension, even though she knew you'd been procrastinating. You said something insensitive to your spouse, but instead of retaliating, she kept quiet and didn't hold it against you the next day. One-way love is the essence of any lasting transformation that takes place in human experience—a person loved in weakness blossoms.

So we might say reasons answer the "why" question and motivations the "how." As I mentioned earlier, we love God because he first loved us. God's command to love him is all the reason we need to love him, but it's not what causes actual love for him. What causes actual love for God is God's love for us. His love for us is what motivates love from us. Reasons, therefore, can differ, but the true motivation always remains the same. As a pastor, I always counsel people to "run to the cross" because the love found there—the one-way love of God in Christ—is the only truly motivating factor toward Christian obedience.

Matt Smethurst serves as associate editor for The Gospel Coalition and lives in Louisville, Kentucky. You can follow him on Twitter.

http://thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/tgc/2013/10/09/you-cant-exhaust-it/