Conference of Italian Bishops

Conference of Italian Bishops

'Jesus, Our Contemporary'

Rome, February 2012

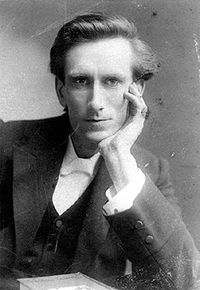

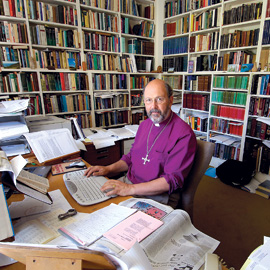

Main Paper by the Right Reverend Professor N. T. Wright,

University of St Andrews

'Christ is Risen from the Dead, the First Fruits of Those who have Died'

Introduction

I am very grateful for the invitation to participate in this assembly, and for your welcome and hospitality to my wife and myself. It is good to be here in Rome once again, and among friends.

I am particularly glad to be able to say something on the subject of the Resurrection of Jesus, within the overall topic of 'Jesus, our Contemporary'. There is already here a considerable paradox. On the one hand, it is precisely because Jesus is risen from the dead that he is alive in a new, unique way; that he is able to be with us as a living presence, which we know in prayer and silence, in reading scripture and in the sacraments, and (not least) in the service of the poor. All those things he has promised us, and his promises do not fail. He is, in that sense, truly our contemporary. But at the same time, as our title indicates, in his resurrection Jesus stands over against us. He is different. He is the first fruits; we are the harvest that still awaits. He has gone on ahead while we wait behind. What is more, the meaning of his resurrection cannot be reduced to anything so comfortable as simple regarding him as 'contemporary' in the sense of a friend beside us, a smiling and comforting presence. Because he is raised from the dead, he is Lord of the world, sovereign over the whole cosmos, the one before whom we bow the knee, believing that in the end every creature will come to do so as well.

The title I have been given is a quotation from St Paul, in the first letter to the Corinthians. This is a famous and central passage and I shall return to it in due course. But I want to begin with some wider reflections about the resurrection: about the event and its meaning. I want to draw out some of the challenges we meet today when speaking of the resurrection not only in the wider world, where the idea is of course still mocked, but also in the church, where we have had a bad habit of belittling and domesticating this most explosive of all moments.

1. Resurrection in the First Century

We begin with the central meaning of resurrection in the first century. After generations of confusion we must reaffirm that the Greek word anastasis and its cognates really do refer to a new bodily life given to a human body that had been dead. Anastasis was not a clever or metaphorical way of speaking of a 'spiritual' or 'non-bodily' survival of death. The ancient Greeks and Romans had plenty of ways of speaking of such a thing, and anastasis was not one of them. Some people still suggest that when the first disciples said that Jesus had been raised from the dead what they really meant was that his cause, his kingdom-agenda, would continue, or that they had a sense of his continuing presence with them, forgiving them their failures and encouraging them to carry on with his work. Well, they did indeed believe his kingdom-agenda was going on, and they did believe he had reconstituted them to carry that work forward; but the reason they believed both of those things was because they really did believe he had been bodily raised from the dead, leaving an empty tomb behind him. This was not, as is sometimes suggested, a mere 'resuscitation', a return to exactly the same sort of bodily life as before; but nor was it a translation into a non-bodily mode. When Paul describes the resurrection body as 'spiritual', the word he uses does not mean 'a body composed ofspirit', but 'a body animated by spirit' - or, in this case, by God's spirit.

I have argued elsewhere that we cannot understand the historical rise of the early Christian movement unless we take as basic their belief that Jesus really was raised in this bodily sense. Of course, one might say that they were mistaken; but I have also argued that the best reason for the rise of that belief is that it really did happen. The other explanations - that the disciples were the victims of a delusion, that one or more of them saw a vision of Jesus such as has often been reported by people after someone they love has died, and so on - simply do not hold water historically. To mention only the last of these: such visions were as well known in the ancient world as they are today, and the meaning of a vision like that was not that the person was suddenly alive again, but rather that they were indeed well and truly dead.

But I want to move on from that argument. This is not only because I and others have made the case at some length already. It is also because it is easy to be distracted by the question 'but did it happen?' from the question 'but what does it mean?' As we consider Jesus our contemporary, the event remains vital but the meaning is all-important. We in the church have often downgraded the meaning into terms of private spirituality or the hope of heaven; but it goes far deeper and wider than that.

The question 'But did it happen?' was the question asked by the Enlightenment, not only about the resurrection but about a great deal besides. Some devout Christians have shied away from this question, believing with Proverbs 26.4 that if you answer a fool according to his folly you will be a fool yourself. In this instance, I have taken the opposite view, based on Proverbs 26.5, that you must answer the fool according to his folly, otherwise he will be wise in his own eyes. It remains enormously important that we investigate the historical origins of Christianity. As the Holy Father himself has insisted, what actually happened in the first century matters, because we are not Gnostics: we believe in a God who came into the very stuff and substance of our flesh and blood and died a real death. Yes, and rose again three days later.

My argument, however, is not that we can somehow 'prove' the resurrection of Jesus according to some neutral, objective canon of plausibility. That would, indeed, be to capitulate to the folly of the Enlightenment. My argument, rather, is that we can, by historical investigation, reveal the folly of all the other explanations that are sometimes given for how Christianity got going in the first place. This forces us back to the much larger question, which of course the Enlightenment did not want to face: might it after all be the case that the closed worldview of some modern science is incorrect, and that the world is after all created by and loved by a God who is not distant, detached and unable to act within the world, but rather by a creator who remains mysteriously present and active within the world in a thousand ways, some of them dramatic and unexpected?

I have often used as an illustration the idea of a college or school being given a wonderful painting by an old member. The painting is so magnificent that it must be displayed, but there is nowhere in the present college buildings that will do it justice. Eventually the college decides to pull down some of its main buildings and rebuild them with this picture as the central feature. Then, in doing so, they discover that several things nobody really liked about the college the way it used to be - the layout, the architecture, the inconvenient rooms - were solved in the new arrangement. The gift was rightly given to the college, but the college, in order to accept it, had itself to be transformed. That, I suggest, is what happens with the resurrection. You can't fit it (of course) into the modernist worldview of the European Enlightenment. But, when you dismantle the eighteenth-century Deism which insists on God and the world being utterly separate, and when you demolish the pseudo-scientific prejudice which says that the space-time world is a closed continuum of cause and effect, you find that not only will the resurrection of Jesus make excellent sense; it will address, and help you solve, all kinds of other things about the modern worldview which have caused, and still cause, problems. We might, for a start, look at the modern western systems of democracy and finance . . .

But to return to the first century. Many Jews (not all) believed in bodily resurrection as the ultimate destiny of all God's people, perhaps of all people. They clearly meantbodily resurrection, as we see (for instance) in II Maccabees 7. But it won't do simply to say that the early Christians, being devout Jews, reached for that category in their grief after the death of Jesus. The early Christian view of resurrection is utterly Jewish, but significantly different from anything we find in pre-Christian Judaism. There, 'resurrection' was something that was supposed to happen to everyone at the end, not to one person in the middle of history. Nor had anyone prior to the early Christians formulated the idea that resurrection might mean the transformation of a human body so that it was now still firmly a human body but also beyond the reach of corruption, decay and death. Nor was there in early Christianity, as there was in Judaism, a spectrum of belief about life after death. They all believed in resurrection - that is, in a two-stage post mortem reality: that those who belonged to Jesus would die, would then rest 'in the hand of God' (Wisdom 3.1), and would then at a later stage be raised. In some of my writings I have referred to the first stage as 'life after death', and to the second as 'life after life after death'.

One of the most striking differences between Christian belief and pre-Christian Jewish belief is that nobody expected the Messiah to be raised from the dead - for the obvious reason that nobody expected the Messiah to be killed in the first place. We have evidence for plenty of messianic or would-be messianic movements in the century or so either side of Jesus. They routinely ended with the violent death of the founder. When that happened, his followers faced a choice: give up the movement, or find yourself a new leader. We have evidence of both. Going around saying your leader had been raised from the dead was not an option. Except in the case of the followers of Jesus of Nazareth.

I conclude from all this - which could of course be spelled out at much more length - that we can only understand early Christianity as a movement that emerges from within first-century Judaism, but that it is so unlike anything else we know in first-century Judaism (and the unliknesses bear no resemblance to anything in the pagan world) that we are forced to ask what caused these mutations. The only plausible answer is that they were caused by the actual bodily resurrection, into a transformed physicality, of Jesus himself. Put that in place, and everything is explained. Take it away, and everything remains puzzling and confused. Of course, there is a cost. One cannot simply say, 'Well, it looks as though Jesus of Nazareth was raised from the dead' and carry on with business as usual. If it happened, it means that a new world has been born. That, ultimately, is the good news of Easter, the good news which the rationalism of the Enlightenment has tried to screen out and which the church, tragically, has often forgotten as well. But to address this we need to move to the next section of this lecture.

2. From Event to Meaning: The Four Gospels

I suggest, in fact, that the rationalistic question 'But did it happen?', though highly important and deserving of an answer, has also often functioned to prevent us thinking through the question of what the resurrection of Jesus meant, and still means. The church has often been content to do two things side by side: first, to 'prove' the resurrection by a more or less rationalistic argument; second, to say that therefore 'Jesus is alive today, and we can get to know him', or perhaps also, 'therefore Jesus is the second person of the Trinity'. One also frequently hears, especially in Easter sermons, 'Jesus has been raised, therefore we too are going to heaven'. All this is a way of saying, within the same eighteenth-century framework, that the Christian claim is true and the sceptical claims are false.

That is fine as far as it goes. But it doesn't go nearly far enough. And in fact, interestingly, the New Testament itself does not make those connections in the same way. There is a real danger that we will simply short-circuit the process and force the resurrection to mean what we want it to mean, without paying close attention to what the first Christians actually said. In the closing chapters of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, and in the opening chapter of Acts, we do not find anyone saying that because Jesus is alive again we can now get to know him, or that he is the second person of the Trinity (though Thomas does say 'My Lord and my God'). We do not, in particular, hear anyone in the gospels saying that because Jesus has been raised we are assured of our place in heaven. What we do hear, loud and clear in the resurrection narratives and in the early theology of Paul, is something like this.

To begin with, Jesus was crucified as a messianic pretender; all the gospels say that the words 'King of the Jews' were stuck up above his head. The resurrection appears, then, to reverse the verdict of the Jewish court and the Roman trial: Jesus really was God's Messiah. But at this point hardly any modern Christians have realised the significance of the Jewish vision of the Messiah, going back to passages like Isaiah 11 and Psalms 2 and 72. The point about Israel's Messiah is that when he appears he will be king, not of Israel only, but of the whole world. Paul's vision, that 'at the name of Jesus every knee shall bow', is an essentially messianic vision before it is even a vision of Jesus as the second person of the Trinity, though it is that as well, and Paul believed the two were made to fit together.

But unless we grasp the essentially Jewish vision of Messiahship, and the early Christian belief that Jesus was the Messiah based on his resurrection, we won't get to the heart of it. 'Jesus our contemporary' is Jesus the Jew, Jesus the Messiah, Jesus the one who launched God's kingdom on earth as in heaven. For many centuries the western church has done its best to avoid the plain meaning of the four gospels, and the Enlightenment pushed us further away yet. The gospels build on the ancient Jewish belief that God's call to Abraham was the call of a people through whom he would rescue humans and the world from their plight. The long history of that people often seemed to have lost its way, but the four gospels tell the story of Jesus, climaxing in his death and resurrection, as the story of how God's plan for Israel, and his plan through Israel for the world, was fulfilled at last. The resurrection of Jesus means what it means in the four gospels because it is the fulfilment of that vision and hope. It is the moment when, as Jesus himself explains to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, all that the prophets had spoken was now fulfilled. 'We had hoped,' said the sad and puzzled pair, 'that he was the one to redeem Israel'; and now the risen Jesus explains that he has not only redeemed Israel but is sending this redeemed Israel - his Spirit-equipped and scripturally-taught followers - out into the world with the message that Israel's God is its true and rescuing lord and king.

If Jesus' resurrection is the fulfilment of Israel's story, it is also, and for the same reason, the fulfilment of the story of God himself. Here we have to be careful. How easy it is for us, with our developed Trinitarian theology, to rush in with Augustine or Aquinas, with Gregory or Athanasius. Let's put that on hold for the moment and think about how first-century Jews were telling the story of Israel's God. Israel's God had abandoned Jerusalem and the Temple at the time of the exile. Ezekiel, who describes the divine glory leaving the Temple, promises that this glory will return, but never tells us that it's happened. In fact, several prophets speak of YHWH coming back to Zion as the climax of the return from exile, but nowhere does anyone say it's happened. Isaiah spoke of 'the glory of YHWH being revealed, and all flesh seeing it together' (40.5), and of Jerusalem's watchmen shouting for joy because they could see YHWH in plain sight, returning to Zion (52.8). But nobody ever suggested, throughout the four centuries of post-exilic Judaism, that it had happened at last. Zechariah says it will happen (14.5). Malachi, addressing the bored priests, insists that 'The Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple' (3.1). But he hasn't done so yet.

But the evangelists tell the story of Jesus precisely as the story of how YHWH returned to Zion at last, unexpectedly, shockingly and shamefully. That isn't our subject today, but I suggest that this, with all its overtones of the Jewish expectation of Israel's God returning to the Temple, is at the very heart of New Testament Christology. Suffice it to say that when we come to the resurrection accounts, the case has already been made. Matthew and Mark insist that at Jesus' baptism the prophecies of Isaiah and Malachi began to be fulfilled. Luke says that when Jesus came to Jerusalem the residents did not know the time of their divine visitation. This, in other words, was the moment when YHWH came back at last. John says 'the word became flesh, and tabernacled in our midst, and we beheld his glory' (1.14): in other words, Jesus is the revelation of God's glory, returning to his people at last in the form of the temple which is his body. That is the reason why, balancing that opening statement in John 1.14, we find Thomas in 20.28 declaring 'My Lord and my God'. He is seeing and recognising the glory of God in the face, and in the wounded hands and side, of the risen Jesus. We never knew God's glory would look like that.

You see, it is all too easy for us to slip into a form of docetism at this point: to think, simply, 'Well, the resurrection proves that Jesus is divine', and to forget the rich human dimensions of the story. But our theme this week demands that we recognise in the resurrection that (so to speak) the divine is Jesus: that in the man from Nazareth we see not only Jesus our contemporary but also God our contemporary. We recognise God standing before us, wounded for our trespasses and bruised for our iniquities, and we hear the prophet say, 'Who would have thought that he was the Arm of the Lord?'

So if Jesus' resurrection, in the gospels, is the point where Israel's story and even God's story come to their final climax, it is also of necessity the moment when the church is truly born. Of course, there is a sense in which the church is born with the call of Abraham; another sense in which the key moment is the call of the first disciples; another again in which Pentecost is all-important. But we cannot read the stories of the resurrection without realising that this is the great turning-point, when a bunch of frightened and muddled men and women stumbled despite themselves on the truth that world history had turned its greatest corner, that a new power was let loose in the world, that a door had been opened which no-one could shut. The church was born in that moment, not as an institution, not as an inward-looking safe group, but precisely as a surprised gaggle of people coming to terms with something far bigger than they had dared or wanted to imagine. The church was born as Mary, Peter and John ran to and fro in the half-light, half-believing and with tears and questions. The church was born at the moment when the two disciples at Emmaus recognised the stranger as he broke the loaf. The church was born as the angel told Jesus' followers to hurry to Galilee because he was already on his way there. The church was born as he opened their minds to understand the scriptures. And all of this is in service of the mission of the kingdom. Something has happened in the resurrection because of which Jesus is now the challenging contemporary not only of his first followers, but of the whole world. He goes before us still, and we have to hurry to catch him up.

Finally, therefore, the resurrection stories bring to a head - by implication, but when we learn to read the gospels properly the implication is very clear - the challenge of the kingdom of God to the kingdoms of the world. Here I must, with the greatest respect and admiration, take issue with the Holy Father in his suggestion that the achievement of Jesus was to separate the religious from the political. Of course there is a sense in which that is true, as the limitless depths of divine love invite us to a lifetime of exploration which utterly transcends all human life and national and international organisation. But each of the evangelists, in their own ways, tells the story of Jesus as the story of confrontation between Jesus and the Herod family, between Jesus and Caesar or his representatives, and behind them between Jesus and the dark satanic powers who shriek at him or plot against him. It was the powers of the world, spiritual but also political, that put Jesus on the cross, and the resurrection of Jesus our contemporary is therefore the victory of Jesus over all the powers of the world. On Good Friday morning, in John 18 and 19, he argued with Pontius Pilate about kingdom, truth and power, and when John goes on to tell the story of the resurrection he wants us to see that kingdom, truth and power are reborn in Jesus in a new form. It is then part of the church's task to work out what that will mean.

That is why Paul, our earliest written witness, links the resurrection directly and messianically to the world sovereignty that is now claimed by Jesus. At the climax of the theological argument of the letter to the Romans, he quotes Isaiah 11: the root of Jesse rises - resurrects! - to rule the nations, and in him the nations shall hope. And that looks back to, and confirms the interpretation of, the very opening of Romans, in which the resurrection has publicly established Jesus, the Davidic Messiah, as 'son of God in power' - in a world where 'son of God' meant, unambiguously, Caesar himself. The political meaning of the resurrection is, I think, one of the most profound reasons why, in the philosophy of the Enlightenment, the question was pushed back, sneeringly, at the church: but did it happen? The Enlightenment philosophy, which has shaped our contemporary world so radically, insisted that world history had turned its great corner in Europe and America in the eighteenth century. It was, say the American dollar bills to this day, 'a new saeculum'. But if it is true that Jesus was raised from the dead then it is Easter that is the great turning-point of world history. World history cannot have two fulcrum moments. The Enlightenment's own agenda was to banish God upstairs out of sight, so that enlightened modern man could run the world in his own way - and we have seen what a mess that has produced, precisely where the Enlightenment was most at home. The church has gone along for the ride, content to play out its private spirituality with a contemporary Jesus who has been only a shadow of his true self. But the truly contemporary Jesus is the one who confronts all the pretensions of today's power just as he confronted Pontius Pilate that first Good Friday; and the resurrection is the sign that his kingdom, his truth and his power were the right kind. As the grandiose ambitions of the European and American Enlightenment look more and more threadbare, it is incumbent on the church to explore afresh the social, cultural and political tasks to which we are committed by the resurrection of Jesus our contemporary.

3. From Event to Meaning: Paul

I turn now to the passage from which my title is taken, 1 Corinthians 15. 'The Messiah has been raised from the dead, as the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep.' The first fruits are offered, at the beginning of the harvest, as the sign that there is much more to come. So it is with the Messiah, as we have already seen: he has gone on ahead, and the rest of us will follow. This is one of the great Christian innovations in eschatology: the notion of 'resurrection' has split in two, and we live in between those two - Jesus' resurrection and our own - not indeed as passive spectators of an apocalyptic drama, but as active participants. Jesus our contemporary enlists those who believe in him in what we might call his resurrection project, his kingdom-project, his task of bringing his sovereign and saving rule to bear on the whole world.

The point of 1 Corinthians 15 is, after all, to locate the future resurrection of believers within the larger worldview of God's kingdom. Verses 20-28 are Paul's classic statement of the kingdom of God, carefully nuanced: at the moment Jesus is reigning, is ruling the world, and when he has finished by overcoming death itself he will then hand the kingdom over to the Father, so that God may be 'all in all'. To be grasped by the risen Jesus as our contemporary must mean being grasped by this kingdom-vision, from which the western church, both Catholic and Protestant, has so often and so sadly retreated. Of course, to our secular contemporaries it makes no sense to suggest that Jesus is in charge of the world, and has been since Easter. Most people look at the continuation of violence, deceit and chaos over the last two thousand years and say it's ridiculous to say that Jesus is in charge. But when we read the gospels we get a different sense. Think of the Beatitudes, not primarily as offering a blessing to those who are described, but through them to the world. This is how Jesus wants to run the world: by calling people to be peacemakers, gentle, lowly, hungry for justice. When God wants to change the world, he doesn't send in the tanks; he sends in the meek, the pure in heart, those who weep for the world's sorrows and ache for its wrongs. And by the time the power-brokers notice what's going on, Jesus' followers have set up schools and hospitals, they have fed the hungry and cared for the orphans and the widows. That's what the early church was known for, and it's why they turned the world upside down. In the early centuries the main thing that emperors knew about bishops was that they were always taking the side of the poor. Wouldn't it be good if it were the same today. Death is the last enemy, according to Paul in this chapter, and we live in a world that still deals in death as its main currency. If we claim Jesus as our contemporary, we claim to know and love the one who has defeated death itself, not with more death, not with superior killing power, but with the power of love and new creation.

There is more, much more, in what Paul says about Jesus our risen contemporary. I hardly dare make this point but I must. As far as Paul is concerned, Jesus is the onlyhuman being who has so far been raised from the dead, and he does not expect anyone else to be resurrected until the Parousia. I suspect that other ideas crept in many centuries later, not least once the mediaeval church lost its grip on resurrection itself and reverted to what was basically an ancient pagan scheme of a blissful and disembodied heaven and a terrible hell. That is a subject for another time. But for Paul it is Jesus himself who is our contemporary, ruling already and planning to return to complete his reign on earth as in heaven. Christ is risen from the dead, the firstfruits of those who sleep; and we who celebrate him as our contemporary are charged to work with him on his kingdom-project in the present time. 1 Corinthians 15 is a spectacular chapter, but one of the most remarkable verses in it is the last (verse 58), where Paul doesn't say 'therefore enjoy the presence of Christ', though he might have done, or 'therefore look forward to your glorious future', though he might have said that as well. He says 'therefore get on with your work in the present, because in the Lord your labour is not in vain.' That is at the heart of the meaning of the resurrection. Because God is already making his new creation, all that you do in Christ and by the Spirit is part of that new world. Every cup of cold water, every tiny prayer, every confrontation with the bullies who oppress the poor, every song of praise or dance of joy, every work of art and music - nothing is wasted. The resurrection will reaffirm it, in ways we cannot begin to imagine, as part of God's new world. Resurrection isn't just about a glorious future. It is about a meaningful present. That is what it means that Jesus, our contemporary, is raised from the dead as the firstfruits of those who slept.

4. Conclusion: Resurrection and Vocation

I have said what I want to say, but I cannot stop right there. Come back with me, as I close, to John's gospel, and to those final two chapters where we see the risen Jesus meeting three key people: Mary, Thomas and then Peter. To know the risen Jesus as our contemporary is to know him in these ways, always mysterious, always deeply challenging. Much more could be said on each, but I hope these brief reflections serve to anchor and focus our entire theme.

First, Mary Magdalene. She is the first to see the risen Lord, and she mistakes him for the gardener. Quite right, too: because, for John, this is the beginning of new creation, with the light breaking through into the darkness of the early morning garden. Jesus and Mary are not exactly the new Adam and Eve, but the resonances of the first garden, and of the healing of its ancient wound, are powerfully present. And, as Mary looks through her tears and sees, first the angels and then Jesus himself, we recognise not just a new reality but a new way of knowing that reality: a new creation which is to be known by the mourners, those who weep for their loss, for the world's loss. And Jesus' answer to her stumbling question is more powerful than our translations can acknowledge. Up to now, in most texts, Mary has been referred to by her Greek name, Maria; but now, in most manuscripts, Jesus calls her by her Aramaic name, Mariam: her original name, the name her parents called her, his mother's name. And in that fresh naming there is also a commission: Mary, Miriam, is to be the apostle to the apostles, the first to announce to anyone else that he is risen, that he is to be enthroned as Lord of the world. There is an ocean of vocational reflection there in which we can swim at our leisure.

Second, Thomas. Thomas is quite different from Mary. No tears; just stubborn resistance. He demands evidence. He wants to see, to touch. Thomas stands for so many in ourculture who still ask, with the Enlightenment (though of course the impetus is much older) 'But is it true?' He doesn't want to live in the imagined fantasy-world of someone else's story. Reality or nothing for him - and fair enough, since Israel's God is the creator and Israel's hope is for the renewal of creation, not for an escape from creation into an imagined world of fantasy. And Jesus meets Thomas fair and square. He doesn't say, as some theologians today would say, 'No, Thomas, you're coming at it the wrong way; we don't do scientific evidence here, you need a different epistemology.' Yes, there is a gentle but firm rebuke: Blessed are those who have not seen, and yet believe. But this only comes after Jesus has first offered Thomas his hands and his side. Evidence you want? Evidence you shall have. We are not told, however, that Thomas did actually reach out his hand to touch. Instead, he takes a flying leap past anything the others had yet said. Sometimes it is the doubters who, when convinced, become the most insightful.'My Lord and my God!' It is the climax of the gospel; and I invite you to reflect on the fact that it might not have happened this way had Thomas not asked his question. I see there at least the beginnings of a parable about the nature of knowledge, of all knowledge, in our own day.

Finally, Peter. You are familiar, of course, with the story of the breakfast by the shore, and I'm sure you are aware that the charcoal fire in John 21.9 is meant to remind us, the readers, of the terrible moment in the High Priest's hall by another charcoal fire (John 18.18), when Peter three times denied even knowing Jesus. No doubt the smell of it reminded Peter of that moment as well. If this little story is the beginning of the true Petrine ministry, as some have suggested, then we do well to notice that this ministry begins with confrontation and penitence. 'Simon, son of John, do you love me?'

It is a question we all face, perhaps particularly those of us called to ministry and leadership within the church. If we know our own hearts - and woe betide a church that is led by people who do not - we know that we have all let Jesus down, that our hearts and minds have plenty of memories of our own charcoal fires, of the times when by our actions or words we have in effect denied that we even knew Jesus. Yet Jesus comes, and comes again, and asks us the same question. 'Do you love me?'

The Greek text makes it quite clear that Peter's response uses a different word. He can't bring himself to say the word agapao, the word for that utter self-giving love that Jesus himself has shown on the cross. He uses the word phileo: 'Yes, Lord,' he says, 'You know I'm your friend.' That's as far as he can go. Anything else would seem to be back in the realm of blustering, of boasting: 'Yes, Lord, I'm OK, I can do anything for you.' That's what he'd said in the Upper Room (13.36-37). He is going to start further back.

But then the miracle: 'Well then,' replies Jesus, 'feed my lambs.' This is the moment we as pastors and church leaders need to note most closely, the moment when the risen Jesus becomes once more our uncomfortable contemporary. We expect, perhaps, a note of rebuke: 'Why did you let me down?' We might hope for a word of forgiveness: 'Peter, you let me down, but I forgive you.' What we do not expect is a fresh word of commission: 'Feed my lambs.' Here is the miracle of resurrection as it applies directly to vocation. All vocation to be pastors in the church of the risen Jesus comes in the form of forgiveness. Forgiveness and commission turn out to be the same thing. Forgiveness never simply brings us back to a neutral position; and commission can never be on the basis that we are good people, well qualified, fully prepared for what we have to do. That was Peter's problem before. Now he begins again in the proper way: with penitence, forgiveness, and fresh commission. That is the gift of the risen Jesus to Peter, and please God to us as well.

But it doesn't stop there. Jesus asks the same question a second time and gets the same answer, this time responding with 'look after my sheep.' But then, on the third occasion, Jesus changes the question. Peter has said, 'Yes, Lord, you know I'm your friend.' Now Jesus asks, 'Simon, son of John, are you my friend?' John, telling the story, indicates that Peter was upset that on this third occasion Jesus used these words. Perhaps he thought Jesus didn't believe him, that he was challenging even the lesser claim that he had made. I don't read it like that. I think Jesus is saying, in effect, 'Very well, Peter: if that's where you are, that's where we'll start. If you can say you're my friend, we will build on that. Now: feed my sheep.' And then, of course, he goes on to warn Peter of what is to come; this sheep-feeding business will cost him not less than everything, as it had cost the master Shepherd himself.

But this, for me, stands at the heart of the message of Jesus our contemporary, the one who is risen from the dead as the first-fruits of those who sleep. With the resurrection, a new creation has dawned, and in that new creation new possibilities are open before us. The resurrection is not the end of the story; it's the beginning of the new one, precisely because Jesus is the first-fruits and the full harvest is yet to come. And we who are called to work within that new creation, from the Petrine ministry through to all other ministries, find those ministries not in a grandiose claim or the blustering confidence that Peter had shown in the days before Jesus' death. We find our ministries given to us afresh day by day as we confess our own failures and yet come, humbly, and say, 'Yes, Lord, you know I'm your friend.' Resurrection and forgiveness are, after all, two sides of the same coin; to believe in the one, you have to believe in the other. As Ludwig Wittgenstein said, it is love that believes the resurrection. Here in John's gospel, in Mary, in Thomas, and above all in Peter, we discover what it means to know the risen Jesus as our contemporary, wiping away our tears, answering our hard questions, but above all inviting us to come with the humility and the love through which the power of his risen life, his shepherding of his sheep, can go to work afresh in our own day. This is what it means to know the risen Jesus as our contemporary. 'Yes, Lord,' we say. 'You know.' 'Well, then,' replies Jesus, 'feed my sheep.'

Full details on more or less all aspects of what follows can be found in N. T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God (London and Minneapolis: SPCK and Fortress Press, 2003); Italian translation ; or Surprised by Hope (London and San Francisco: SPCK and HarperSanFrancisco, 2007).

In any case, even 'spirit', in the world of Paul and his hearers, would most likely have been understood in a quasi-physical manner, in line with Stoic philosophy; but that's another matter.

Luke 24.21, 25-27, 44-49; Acts 1.6-8.