"THE PLAN"

"THE PLAN"

MEN and women today feel lost and astray in this world. A glance at our modern art, poetry or novels, or five minutes' conversation with a sensitive unbeliever, will assure us of that. In an age that has won a higher degree of control over the forces of nature than any before, this may seem odd; but it is not really odd. It is God's judgment, which we have brought down on ourselves by trying to feel too much at home in this world.

For that is what we have done. We have set our faces against the idea that one should live on the basis that there is something more than this world to live for. Even if we privately thought that the materialists were wrong in denying God and another world exist, we have not allowed our belief to stop us living on materialistic principles: treating this world as if it were the only home we should ever have, and concentrating exclusively on arranging it to our comfort. We thought we could build heaven on earth, and tried. And now God has judged us for our impiety. In less than half a century, we have had two "hot" world wars and one "cold" one, and now we find ourselves in the age of such horrors as nuclear warfare and brainwashing. In such a world, it is not possible to feel at home. It is a world which has disappointed us. We expected life to be friendly (why? - but we did); instead, however, it has mocked our hopes and left us disillusioned and baffled. We thought we knew what to make of life, but now we do not know whether anything can be made of it. We thought of ourselves as wise men, but now we find ourselves like benighted children, lost in the dark.

Sooner or later, this was bound to happen; for God's world is never friendly to those who forget its Maker. The Buddhists, who link their atheism with a thorough pessimism about life, are to that extent right. Without God, man loses his bearings in this world, and he cannot find them again till he has found the One whose world it is. God made our life, and God alone can tell us its meaning. If we are ever to make sense of life in this world, we must know about God. And if we want to know the facts about God, we shall be wise to turn to the Bible.

Reading the Bible

Let us read the Bible then - if we can. But can we? The truth is that many of us have lost the ability to read the Bible. When we open our Bibles, we do so in a frame of mind which forms an insuperable barrier to our ever reading it at all. This may sound startling, but it is not hard to show that it is true.

When you sit down to any other book, you treat it as a unit. You look for the plot, or the main thread of the argument, and follow it through to the end. You let the author's mind lead yours. Whether or not you allow yourself to "dip" before settling down to the book properly, you know that you will not have understood it till you have been through it from start to finish, and if it is a book that you want to understand you set aside time to read it in full. But when we come to Holy Scripture, our behaviour is different. In the first place, we are in the habit of not treating it as a book - a unit - at all, but simply as a collection of separate stories and sayings. We take it for granted before we look at the text that the burden of them - or, at least, of as many of them as affect us - is either moral advice or comfort for those in trouble. So we read them (when we do) in small doses, a few verses at a time. We do not go through individual books, let alone the two complete Testaments, as a single whole. We browse through the rich old Jacobean periods of the Authorised Version, waiting for something to strike us. When the words bring to our minds a soothing thought or a pleasant picture, we feel that the Bible has done its job for us. It seems that the Bible is for us not a book, but a collection of beautiful and suggestive snippets, and it is as such that we use it. The result is that we never read the Bible at all. We take it for granted that we are handling Holy Writ in the truly religious way; but in truth, our use of it is more than a little superstitious. It is the way of natural religiosity, perhaps, but not of true religion.

For God does not mean Bible-reading to function simply as a drug for fretful minds. The reading of Scripture is intended to awaken our minds, not to send them to sleep. God asks us to approach Scripture as His Word - a message addressed to rational creatures, men with minds; a message which we cannot expect to understand without thinking about it. "Come now, and let us reason together," said God to Judah through Isaiah (Isa. 1:18), and He says the same to us every time we take up His book. He has, indeed, taught us to pray for divine enlightenment as we read - "open thou mine eyes, that I may behold wondrous things out of thy law" (Ps. 119:18); but this is a prayer that God will enable us to think about His Word with insight, and we effectively prevent its being answered if after offering it we make our minds a blank and stop thinking as we read. Again, God asks us to read the Bible as a book - a single story with a single theme. We are to read it as a whole, and as we read, we are to ask ourselves: what is the plot of this book? What is its real subject? What is it really about? Unless we ask these questions, we shall never reach the point from which we can see what it is saying to us about our own individual lives.

When we do reach this point, we shall find that God's real message to us is more drastic, and at the same time more heartening, than anything that human religiosity could conceive.

The Main Theme

What do we find when we try to read the Bible as a single unified whole, with our minds alert to observe what it is really about?

The first thing we find is that this book is not primarily about man at all. Its subject is God. He (if the phrase may be allowed) is the chief actor in the drama, the hero of the story. The Bible proves on inspection to be a factual survey of His work in this world, past, present, and to come, with explanatory comment from prophets, psalmists, wise men and apostles. Its main theme is not human salvation, but the work of God vindicating His purposes and glorifying Himself in a sinful and disordered cosmos by establishing His kingdom and exalting His Son, by creating a people to worship and serve Him, and ultimately by dismantling and re-assembling this order of things, so rooting sin out of His world entirely. It is into this larger perspective that the Bible fits God's work in saving man. And it depicts the God who does these things as more than a distant cosmic architect, more than a ubiquitous heavenly uncle, more than an impersonal life-force - more than any of the petty substitute deities which inhabit our twentieth century minds. He is the living God, present and active everywhere, "glorious in holiness, fearful in praises, doing wonders" (Exod. 15:11). He gives Himself a name - Yahweh (Jehovah: see Exod. 3:14-15; 6:2-3) - which, whether it be translated "I am that I am" or "I will be that I will be" (the Hebrew means both), is a proclamation of His self-existence and self-sufficiency, His omnipotence and His unbounded freedom. This world is His; He made it, and He controls it; He "worketh all things after the counsel of his own will" (Eph. 1:11). His knowledge and dominion extend to the smallest things: "The very hairs of your head are all numbered" (Matt. 10:30). "The LORD reigneth" - the Psalmists make this unchangeable truth the starting-point for their praises again and again (see Psa. 93:1; 96:10; 97:1; 99:1). Though hostile forces rage and chaos threatens, God is King; therefore His people are safe. Such is the God of the Bible.

And the Bible's dominant conviction about Him, a conviction proclaimed from Genesis to Revelation, is that behind and beneath all the apparent confusion of this world lies His plan. That plan concerns the perfecting of a people and the restoring of a world through the mediating action of Christ. God governs human affairs with this end in view, and human history is a record of the outworking of His purposes. It has been truly said that history is - His story. The Bible details the stages in God's plan. God visited Abraham, led him into Canaan, and entered into a covenant relationship with him and his descendants - "an everlasting covenant, to be a God unto thee and to thy seed after thee . . . I will be their God" (Gen. 17:7 f). He gave Abraham a son. He turned Abraham's family into a nation, and led them out of Egypt into a land of their own. Over the centuries He prepared them and the Gentile world for the coming of the Saviour-King, "who verily was foreordained before the foundation of the world, but was manifest in these last times for you, who by him do believe in God" (1 Pet. 1:20f). At last, "when the fulness of the time was come, God sent forth His Son, made of a woman, made under the law, to redeem them that were under the law, that we might receive the adoption of sons" (Gal. 4:4f). The covenant promise to Abraham's seed is now fulfilled to all who put faith in Christ: "if ye be Christ's, then are ye Abraham's seed, and heirs according to the promise" (Gal. 3:29). The plan for this age is that the gospel should go through the world, and "a great multitude . . . of all nations, and kindreds, and peoples, and tongues" (Rev. 7:9) be brought to faith in Christ; after which, at Christ's return, heaven and earth will in some unimaginable way be re-made, and where "the throne of God and of the Lamb" is, there "his servants shall serve him: and they shall see his face . . . and they shall reign for ever and ever" (Rev. 22:3-5).

This is the plan of God, says the Bible. It cannot be thwarted by human sin, because human sin itself is taken up into it, and defiance of God's revealed will is used by God for the furtherance of His will for events. Joseph's brothers, for instance, sold him into Egypt. "Ye thought evil against me," said Joseph afterwards, "but God meant it unto good . . . to save much people alive" (Gen. 50:20); "so it was not you that sent me hither, but God" (Gen. 45:8). The cross of Christ itself is the supreme illustration of this principle. "Him, being delivered by the determinate counsel and foreknowledge of God," said Peter in his Pentecost sermon, "ye . . . by wicked hands have crucified and slain" (Acts 2:23). At Calvary God over-ruled Israel's sin, which He foresaw, as a means to the salvation of the world. Thus it appears that man's lawlessness does not thwart God's plan for His people's redemption; rather, through the wisdom of omnipotence, it is turned to the service of that plan.

Accepting the Plan

This, then, is the God of the Bible, the God with whom we have to do: a God who reigns, who is master of events, and who works out through the stumbling service of His people and the folly of His foes alike His own eternal purpose for His world. And now we begin to see what the Bible really has to say to a generation like our own which feels itself lost and bedevilled in an inscrutably hostile order of things. There is a plan, says the Bible. There is sense in things, but you have missed it. Turn to Christ; seek God; give yourself to the service of His plan, and you will have found the key to living in this world which has hitherto eluded you. "He that followeth me," Christ promises, "shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life" (John 8:12). Henceforth you will have a motive: God's glory. You will have a rule: God's law. You will have a Friend in life and death: God's Son. You will have in yourself the answer to the doubting and despair called forth by the apparent meaninglessness, even malice, of circumstances: the knowledge that "the LORD reigneth," and that "all things work together for good to them that love God, to them that are the called according to his purpose" (Rom. 8:28). Thus, you will have peace.

And the alternative? We may defy and reject God's plan in our unbelief, but we cannot escape it. For one aspect of His plan is the judgment of sin. Those who reject the gospel offer of life through Christ bring upon themselves the dark eternity appointed for all such. Those who choose to be without God shall have what they choose; God respects their choice. But this also is part of the plan, and God's will is done no less in the condemnation of unbelievers than in the salvation of those who put faith in Christ.

Such are the outlines of God's plan, the central message about God which the Bible brings us. Its exhortation to us is that of Eliphaz to Job: "Acquaint now thyself with him, and be at peace; thereby good shall come unto thee" (Job 22:21). In the light of our knowledge that "the LORD reigneth", working out His plan for His world without let or hindrance, we can begin to appreciate both the wisdom of this advice and the glory that lies hidden in this promise.

"ALL THINGS . . . FOR GOOD"

"The Lord reigneth." The Creator is King in His universe. God "worketh all things after the counsel of his own will" (Eph. 1: 11). The decisive factor in world history, the purpose which really controls it and the key which really interprets it, is God's eternal plan. We have seen that the sovereign lordship of God is the basis of the biblical message and the foundation-fact of Christian faith.

But this is a truth which raises problems for sensitive and thoughtful souls at many points. Like other matters of faith, it is not an object of rational demonstration, and circumstances on occasion prompt the most painful doubts about it. Some of the things which happen to God's servants, in particular, hurt and bewilder us: how, we ask, can these misfortunes, these frustrations, these apparent setbacks to God's cause be any part of His will? And we find ourselves tempted when we contemplate events of this sort (of which the Christian world is full) to deny either the reality of God's government or, if not that, at least the perfect goodness of the God who governs. To draw either conclusion would be easy - but it would also be false; and when we are tempted to do so, we should stop and ask ourselves certain questions.

"The Secret Things"

In the first place: ought we to be surprised when we find ourselves for the moment baffled by what God is doing? Surely not. We must not forget what we are. We are not gods; we are creatures, and no more than creatures; and, as creatures, we have no right or reason to expect that at every point we shall be able to comprehend the wisdom of our Creator. He Himself has reminded us, "My thoughts are not your thoughts . . . as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are . . . my thoughts than your thoughts" (Isa. 55:9). Furthermore, the King has made it clear to us that it is not His pleasure to disclose all the details of His policy to His human subjects. As Moses declared, when he had finished expounding to Israel what God had revealed of His will for them - "the secret things belong unto the LORD our God: but those things which are revealed belong unto us . . . that we may do all the words of this law" (Deut. 29:29). The principle illustrated here is that God has disclosed His mind and will so far as we need to know it for practical purposes, and we are to take what He has disclosed as a complete and adequate rule for our faith and life. But there still remain "secret things" which He has not made known and which, in this life at least, He does not intend us to discover. And the reasons behind God's providential dealings sometimes fall into this category.

Job's case illustrates this. Job was never told at any stage about the challenge which God met by allowing Satan to plague His servant in the manner which the book describes. All Job knew was that the omnipotent God was morally perfect and that it would be blasphemously false to deny His goodness under any circumstances. He refused, therefore, to "curse God" even when his livelihood, his children and his health had been taken from him (Job 2:9-10). Fundamentally, in his heart, he maintained this refusal to the end, though the well-meant platitudes which his smug friends churned out at him drove him almost crazy and at times forced out of him wild words about God of which he had later to repent. Though not without a struggle, Job held fast his integrity throughout the time of testing, and maintained his confidence in God's goodness unshaken. And his confidence was in due course vindicated, for when the time of testing ended, after God had come to Job in mercy to renew his humility (40:1-5; 42:1-6), and Job had obediently prayed for the souls of his three maddening friends, it is recorded that "the LORD gave Job twice as much as he had before" (42:10). "Ye have heard of the patience of Job," writes James, "and have seen the end of the Lord; that the Lord is very pitiful, and of tender mercy" (James 5:11). Did the bewildering series of catastrophes that overtook Job mean that God had abdicated His throne, or abandoned His servant? Not at all; as Job in due course proved by experience. But the reason why God had for a time plunged him into darkness was never told him. And may not God, for wise purposes of His own, treat others of His best followers as He treated Job?

But there is more to be said yet.

What is God doing?

In the second place: has God left us entirely in the dark as to what He is doing in His providential government of the world? Indeed, no. He has, in fact, given us extremely full information as to the central purpose which He is executing, and thereby, as we shall see, has given us a very positive rationale of the trying experiences of Christians which constitute our present problem.

What is God doing? In a word, He is "bringing many sons unto glory" (Heb. 2:10). He is saving a great company of sinners. He has been engaged in this task since history began. He first spent many centuries preparing a people and a setting of world-history in readiness for the coming of His Son. Then He sent His Son into the world in order that there might be a gospel, and now He sends His gospel through the world in order that there may be a Church. He has exalted His Son to the throne of the universe, and Christ from His throne now calls sinners to Himself, keeps them, leads them, and finally, brings them to be with Him in His glory. God is saving men and women through His Son: first, by justifying and adopting them into His family for Christ's sake as soon as they believe, thus restoring the relationship between them and Himself which sin had broken; and then, within that restored relationship, by continually working in and upon them to renew them in the image of Christ, so that the family likeness (if the phrase may be allowed) shall appear in them more and more. And it is this renewal of ourselves, progressive here and to be perfected hereafter, which Paul identifies with the "good" for which "all things work together . . . to them that love God . . . the called according to his purpose." For God's purpose, as Paul explains in the next verse, is that those whom God has chosen and in love has called to Himself should "be conformed to the image of his Son, that he (the Son) might be the firstborn among many brethren" (Rom. 8:28-29). All God's ordering of circumstances, Paul tells us, is a means designed for the fulfilment of this purpose. The "good" for which all things work is not, therefore, the immediate ease and comfort of God's children (as is, one fears, too often supposed), but their ultimate holiness and conformity to the likeness of Christ.

Does this help us to understand how adverse circumstances may find a place in God's plan for His people? Certainly, it does; it throws a flood of light upon the whole problem, as the writer to the Hebrews demonstrates. To Christians who had grown disheartened and apathetic under the pressure of constant hardship and victimisation, we find him writing thus: "Have you forgotten the exhortation which addresses you as sons? - 'My son, do not regard lightly the discipline of the Lord, nor lose courage when you are punished [better, reproved, as R.V.] by him. For the Lord disciplines him whom he loves, and chastises every son whom he receives. It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons; for what son is there whom his father does not discipline? . . . We have had earthly fathers to discipline us and we respected them. Shall we not much more be subject to the Father of spirits and live? . . . He disciplines us for our good, that we may share his holiness. For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant; later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it" (Heb. 12:5-11, R.S.V., quoting Prov. 3:11-12). It is striking to see how this writer, like Paul, equates the Christian's "good", not with ease and quiet, but with sanctification. The passage is so plain that it needs no comment, only frequent re-reading whenever we find it hard to believe that whatever the form of rough handling which circumstances (or our fellow-Christians) are giving us can possibly be God's will.

The Purpose of it All

However, there is more to be said still. A third question which we should ask ourselves when the problems of providence distress us is: what is God's ultimate end in His dealings with His children? Is it simply their happiness, or is it something more? The Bible indicates that it is something more. It is the glory of God Himself.

God's end in all His acts is ultimately Himself. There is nothing morally dubious about this; if we allow that man can have no higher end than the glory of God, how can we say anything different about God Himself? The idea that it is somehow unworthy to represent God as aiming at His own glory in all that He does seems to reflect a failure to remember that God and man are not on the same level; and to show lack of realisation that, whereas a man who makes his own well-being his ultimate end does so at the expense of his fellow-creatures, God has determined to glorify Himself by blessing His creatures. His end in redeeming man, we are told, is "the praise of the glory of his grace," or simply "the praise of his glory" (Eph. 1:6, 12, 14). He wills to display His resources of mercy (the "riches" of His grace, and of His glory - "glory" being the sum of His attributes as He reveals them: Eph. 2:17; 3:16) in bringing His saints to their ultimate happiness in the enjoyment of Himself. But we may ask, how does this bear on the problem of providence? In this way: it gives us insight into the way in which God saves us, and suggests the reason why He does not take us to heaven the moment we believe. We see that He leaves us in a world of sin to be tried, tested, belaboured by troubles that threaten to crush us - in order that we may glorify Him by our patience under suffering, and in order that He may display the riches of His grace and call forth new praises from us as He constantly upholds and delivers us. Psalm 107 is a majestic declaration of this.

Is it a hard saying? Not to the man who has learned that his chief end in this world is to "glorify God, and (in so doing) to enjoy Him for ever." To glorify God by patient endurance and to praise Him for His gracious deliverances: to live the whole of one's life, through smooth and rough places alike, in sustained obedience and thanksgiving for mercy received - to seek and find one's deepest joy, not in spiritual lotus eating, but in discovering through each successive storm and conflict the mighty adequacy of Christ to save - and in the sure knowledge that God's way is best, both for our own welfare and for His glory: that is the heart of true religion. No problems of providence will shake the faith of the man who has truly learned this.

THE GLORY OF GOD

God the Creator rules His world for His own glory. "Unto him are all things" (Rom. 11:36); He Himself is the end of all His works. He does not exist for our sake, but we for His. It is the nature and prerogative of God to please Himself, and His revealed good pleasure is to make Himself great in our eyes. "Be still," He says to us, "and know that I am God: I will be exalted among the heathen, I will be exalted in the earth" (Ps. 46:10). God's overriding goal is to glorify Himself.

Its Reasonableness

Now this is a truth which at first we find hard to receive. Our immediate reaction to it is an uncomfortable feeling that such an idea is unworthy of God: that self-concern of any sort is really incompatible with moral perfection, and in particular with God's nature as love. Sensitive and morally cultured people are sincerely shocked by the thought that God's ultimate end is His own glory, and protest most heatedly against it. Why, they say, this is to depict God as essentially no different from a bad man, even from the devil himself! It is an immoral and outrageous doctrine, and if the Bible teaches it, so much the worse for the Bible! Indeed, they often draw this conclusion explicitly with regard to the Old Testament. A volume, it is said, which depicts God so persistently as a "jealous" Being, always concerned first and foremost about His "honour," cannot be regarded as Divine truth, for God is not like that, and it is no less than blasphemy, real if unintentional, to think that He is. Since these convictions are widely and strongly held, it is worth while before we go further to pause and consider what validity they have.

We begin by asking: why are they asserted with so much heat? On other theological questions, men can disagree calmly enough; but it seems a universal experience that protests against the doctrine that God's chief end is His glory are made with passion and rhetoric and even bluster. The reason is not far to seek, and it does credit to the moral earnestness of the speakers. Their outbursts of feeling spring, as passionate outbursts in conversation so often do, from a bad conscience. These persons are sensitive to the sinfulness of continual self-seeking. They know themselves well enough to see that a guilty craving to gratify self is at the root of all their moral weaknesses and shortcomings; they are, indeed, trying as best they can to face it and fight it. A condemning conscience continually reminds them that whenever they seek their own pleasure and aggrandizement, and use their fellow-beings as a means to this end, they do wrong. Hence, they conclude that for God to be self-centred would be equally wrong, and the vehemence with which they reject the idea that the holy God is supremely concerned to exalt Himself reflects their acute sense of the guiltiness of their own past acts of self-seeking.

But is their conclusion valid at all? On reflection, it appears to be a complete mistake. If it is right for man to have the glory of God as his goal, can it be wrong for God to aim at the same goal? If man can have no higher end and motive than God's glory, how can God? And if it is wrong for man to seek a lesser end than this, then it would be wrong for God too. The reason why it cannot be right for man to live for himself, as if he were God, is simply the fact that he is not God; and the reason why it cannot be wrong for God to seek His own glory is simply the fact that He is God. Those who would not have God seek His glory in all things are really asking that He should cease to be God. And there is no greater blasphemy than to will God out of existence.

If the objectors' line of reasoning is so clearly false, why are so many today convinced by it? The appearance of plausibility which this view derives from our inbred sinful habit of making God in our own image, and thinking of Him as if He and we stood, as it were, on the same level, so that His obligations to us and ours to Him correspond; as if He were bound to serve us and further our well-being with the same entire selflessness with which we are in duty bound to serve Him. This is, in effect, to think of God as if He were a man, albeit a great one. If this way of thinking were right, then for God to seek His own glory in everything would indeed make Him comparable to the worst of men and to Satan himself. But our Maker is not a man, not even an omnipotent superman, and this way of thinking of Him is not right. It is, in fact, gross idolatry. (You do not have to make a graven image picturing God as a man to be an idolater; a mental image of this sort is all that you need to break the second commandment.) We must not imagine that the obligations which bind us, as creatures, to Him bind Him, as Creator, equally to us. Dependence, of whatever form, is a one-way relation, and carries with it one-way obligations. Children, for instance, ought to obey their parents - not vice versa! And our dependence as creatures upon our Creator binds us to seek His glory without in the least committing Him to seek ours. For us to glorify Him is always a duty; for Him to bless us is never anything but grace. The only thing that, as God, He is bound to do is the thing that He has bound us to do - to glorify Himself.

We conclude, then, that it is the very reverse of blasphemy to speak of God as self-centred; it would, indeed, be irreligious not to. It is the glory of God to have made all things for Himself and to use them as means for His own exaltation. The clear-headed Christian will insist on this. And he will insist too that it is the glory of man that he is privileged to function as a means to this end. There can be no greater glory for man than to be a means of glorifying God. "Man's chief end is to glorify God" - and it is in so doing that man finds his true dignity as God's creature. The modern humanist, who thinks that man is at his noblest and most god-like when he has thrown off the shackles of religion, imagines that by asserting that man is no more than a means to God's glory we rob human life of all real worth. The truth, however, is the opposite. Human life without God has no real worth; it is a mere monstrosity. But when we say that man is no more than a means to God's glory, we are also saying that man is no less than that - and thus showing how human life can have meaning and value. The only man in this world who enjoys a complete contentment is the man who knows for certain that there is no more worthwhile and satisfying life, no nobler or more significant life, than the life that he is living already; and the only man who knows this is the man who has learned that the way to be truly human is to be truly godly, and whose heart desires nothing more - and nothing less - than to be a means, however humble, to God's chief end - His own glory and praise.

Its Meaning

But what does it mean to say that God's chief end is His glory? To many of us, perhaps, the phrase "the glory of God" is rather empty. With what meaning does the Bible fill it?

The word translated "glory" in the Old Testament originally expressed the idea of weight. From this it came to be applied to that about a person which makes him "weighty" in others' eyes, and prompts them to honour and respect him. Thus, for instance, Jacob's gains and Joseph's wealth are called "glory" (Gen. 31:1; 45:13). Then the word was extended to mean honour and respect itself. Accordingly, the Bible uses it with reference to God in a double connection, speaking, on the one hand, of the glory that belongs to God - the Divine splendour and majesty attaching to all God's revelations of Himself - and, on the other hand, of glory that is given to God - the "honour" and "blessing," praise and worship, which God has a right to receive, and which is the only fit response to the revelation of His holy presence. ["The glory of the God of Israel came . . . and I fell on my face . . ." (Ezek. 43:2f.).] The term "glory" thus connects the thoughts of God's praiseworthiness and of His praise - of the majesty of the revelation of His power and presence from which religion springs, and of the worship which is the right response when we realise that God stands before us, and we before Him.

Take these two thoughts separately for a moment.

(a) In revelation, God shows us His Glory. "Glory" means Deity in manifestation. Creation reveals Him ["the heavens declare the glory of God" (Ps. 19:1); "the whole earth is full of his glory" (Isa. 6:3)]. In Bible times, He disclosed His presence by means of theophanies, which were termed His "glory" (the shining cloud in the tabernacle and temple, Exod. 40:34, 1 Kings 8:10 f.; Ezekiel's vision of the throne and the wheels, Ezek. 1:28; etc.). Believers now behold His glory fully and finally displayed "in the face of Jesus Christ" (2 Cor. 4:6). Wherever we see God in action, there we see His glory - He presents Himself before us as holy and adorable, summoning us to bow down and worship.

(b) In religion, we give God glory. We do this by every act of response to His revelation of grace: by worship and praise ["whoso offereth praise glorifieth me" (Ps. 50:23); "give unto the Lord the glory due unto his name" (Ps. 96:8); " . . . glorify God for his mercy" (Rom. 15:9)]; by believing His Word; by trusting His promises (that was how Abraham gave glory to God, Rom. 4:20); by confessing Christ as Lord, "to the glory of God the Father" (Phil. 2:11); by obeying God's law ["the fruits of righteousness" are to "the glory and praise of God" (Phil. 1:11)]; by bowing to His just condemnation of our sins (so Achan gave God glory, Josh. 7:19f.); and, generally, by seeking in all ways to make Him great (which means making self small) in our daily lives.

Now we are in a position to see what is meant by the statement that God's chief end is His glory. It means that His unchanging purpose is so to display to His rational creatures the glory of His wisdom, power, truth, justice and love that they come to know Him and, knowing Him, to give Him glory for all eternity by love and loyalty, worship and praise, trust and obedience. The kind of fellowship that He intends to create between us and Him is a relationship in which He gives of His fullest riches, and we give of our heartiest thanks, and both to the highest degree. When He declares Himself to be a "jealous" God, and proclaims: "my glory will I not give to another" (Isa. 4:8; 48:11), His concern is to safeguard the purity and richness of this relationship. Such is the goal of God.

And all God's works are means to this end. The only answer that the Bible ever gives to the class of questions that begin: "why did God . . .?" is: for His own glory. It was for this that God decreed to create, and for this that He willed to permit sin. He could have kept man from transgression; He could have barred Satan out of the garden, or have confirmed Adam so that he became incapable of sinning (as He will do to the redeemed in heaven); but He did not. Why? For His own glory. It is often said, most truly, that nothing in God is so glorious as His redeeming love - the mercy which wins back transgressors through the blood-shedding of God's own Son. But there would have been no revelation of redeeming love had sin not been first permitted.

Again: why did God choose to redeem? He need not have done so; He was not bound to take action to save us. His love for sinners, His resolve to give His Son for them, was a free choice which He need never have made. Why did it please Him to love and redeem the unlovely? The Bible tells us why. "To the praise of the glory of his grace . . . to the praise of his glory . . ." (Eph. 1:6, 12, 14).

We see the same purpose determining point after point in the plan of salvation. Some He elects to life, others He leaves under merited judgment, "willing to show his wrath, and to make his power known . . . and that he might make known the riches of his glory on the vessels of mercy . . ." (Rom. 9:22f). He chooses to make up the bulk of His Church from the riff-raff of the world - persons who are "foolish . . . weak . . . base . . . despised." Why? "That no flesh should glory in his presence . . . that, according as it is written, He that glorieth, let him glory in the Lord" (1 Cor. 1:26-31). Why does not God root indwelling sin out of His saints in the first moment of their Christian life, as He will do the moment they die? Why, instead, does He carry on their sanctification with a slowness that is painful to them, so that all their lives they are troubled by besetting sins and never reach the perfection they desire? And why is it His custom to give them a hard passage through this world? The answer is, again, that He does all this for His own glory: to expose to us our own weakness and impotence, so that we may learn how utterly we depend upon His grace, and how limitless are the resources of His saving power. "We have this treasure in earthen vessels," wrote Paul, "that the excellency of the power may be of God, and not of us" (2 Cor. 4:7). We might pursue this line of thought much further, did space permit. Once for all, let us rid our minds of the idea that things are as they are because God cannot help it. God "worketh all things after the counsel of his will" (Eph. 1:11), and all things are as they are because God has chosen that they should be; and the reason for His choice in every case is that it makes for His glory for things to be so.

The Godly Man

In conclusion, let us define what godliness is. We can say straight away that it is not simply a matter of externals, but of the heart; that it is not a natural growth, but a supernatural gift; that it is found only in those who have seen their sin, who have sought and found Christ, who have been born again, who have repented. But this is only to circumscribe and locate godliness; our present question is, what essentially is it? The answer follows from what has already been said. Godliness is the quality of life which exists in those who seek to glorify God.

The godly man does not object to the thought that his highest vocation is to be a means to God's glory; rather, he finds it a source of great satisfaction and contentment. His ambition is to follow out the great formulae in which Paul summed up the practice of Christianity - "glorify God in your body"; "whether therefore ye eat, or drink, or whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God" (1 Cor. 6:20; 10:31). His dearest wish is to exalt God with all that he is in all that he does. He follows in the footsteps of Him who could say at the end of His life here: "I have glorified thee on the earth" (John 17:4), and who told the Jews: "I honour my Father . . . I seek not mine own glory . . ." (John 8:49f.). He thinks of himself in the manner of George Whitefield who said: "Let the name of Whitefield perish, so long as God is glorified." Like God Himself, the godly man is supremely jealous that God, and God only, should be honoured. Indeed this jealousy is a part of the image of God in which he has been renewed. There is now a doxology written on his heart, and he is never so truly himself as when he is praising God for the glorious things that He has done already and pleading with Him to glorify Himself yet further. We may say that it is by his prayers that he is known - to God, if not to men. "What a man is alone on his knees before God," said Murray McCheyne, "that he is, and no more." In this case, however, we must say no less. For prayer in secret is the veritable mainspring of the godly man's life. And when we speak of prayer, we are not referring to the prim, proper, stereotyped, self-regarding formalities which sometimes pass for the real thing. The godly man does not play at prayer, for his heart is in it. Prayer to him is his chief work. And the burden of his prayer is always the same, the expression of his strongest and most constant desire - "Be thou exalted, Lord, in thine own strength." "Be thou exalted, O God, above the heavens." "Father, glorify thy name." "Hallowed be thy name." (Ps. 21:13; 57:5; John 12:28; Matt. 6:9). By this God knows His saints, and by this we may know ourselves.

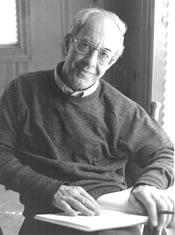

Author

J. I. Packer has had a long-standing passion for the Puritans. Their understanding of God and His ways with man has largely formed his own spirituality and theological outlook.

Educated at Oxford University, Dr. James I. Packer has served as assistant minister at St. John's Church of England, Harborne, Birmingham and Senior Tutor and Principal at Tyndale Hall (an Anglican seminary in Bristol). He preaches and lectures widely in Great Britain and America and contributes frequently to theological periodicals. His writings include Fundamentalism and the Word of God, Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God, and Knowing God. Currently Dr. Packer is Professor of Systematic and Historical Theology at Regent College in Vancouver, British Columbia.