Isaiah 55.8-13; Romans 8.1-11; Matthew 13.1-23

Isaiah 55.8-13; Romans 8.1-11; Matthew 13.1-23

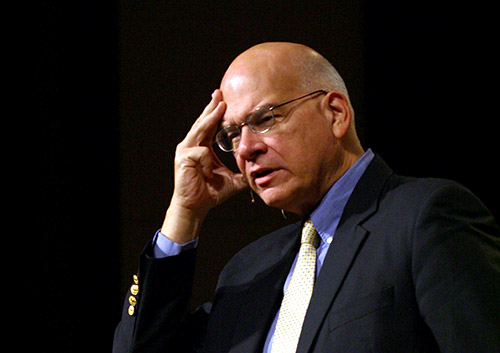

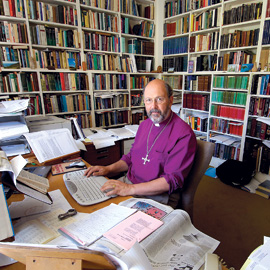

A sermon at Calvary St George, Gramercy Park, New York, on the Third Sunday after Trinity, 10 July 2011, within the celebrations of the Four Hundredth Anniversary of the King James Bible, By the Right Reverend Professor N T Wright, University of St Andrews.

'Ye have seen,' says God to the Israelites, 'what I did unto the Egyptians, and how I bare you on eagles' wings, and brought you unto myself. Now therefore, if ye will obey my voice indeed, and keep my covenant, then ye shall be a peculiar treasure unto me above all people: for all the earth is mine: And ye shall be unto me a kingdom of priests, and an holy nation.' Some of the greatest words of vocation ever uttered: a vocation, indeed, within which all other vocations are contained. God's call to Israel to be his special people for the sake of the world is rooted in his call to Abraham to be the one through whom all the families of the earth would be blessed. And this vital little passage in Exodus 19.4-6 - I was reading, of course, from the King James version - not only provides the motto for our celebrations this weekend, 'on eagles' wings', but also indicates the subtle and powerful way in which the creator God has chosen to work in his world.

And we who celebrate this great anniversary - together with all who worship God this day, whether or not you were aware before this morning that you were stumbling upon a remarkable party - do well to ponder the strange truth of how God works in the world, not only for his people but through his people, and through his people not blindly or despite themselves but through his enlightening, by his word, of their understanding and will. God has not brought the children of Israel out of Egypt for their own sake alone, though freeing slaves is indeed one of God's special delights. He has set them free in order that they may be the people through whom he will set the world free, free to worship God, free to be fully and gloriously human; and the means by which he will do this is through his word at work in them: 'if you will obey my voice indeed, and keep my covenant, then you will be my treasure, my royal priesthood'. The word of God, at work in the redeemed people of God, to equip them for the mission of God. That is the sequence, in Exodus, in Isaiah, in the New Testament, in the work and teaching of Jesus himself. The word at work in the people to set forth the mission.

Our task this morning is not, then, merely to look back in celebration and thanksgiving, as though the Israelites were simply to give thanks for their rescue from Egypt; our task is to discern afresh what it is that God wants to do by his word today and tomorrow, in his people of today and tomorrow, to set forth his mission today and tomorrow. What God has done gloriously through the scriptures, especially the King James Bible within and beyond the English-speaking world of the last four hundred years, God longs to do through his word, through his people, through you and me, in the strange new world that opens up before us in this year of grace 2011. And that is why, though I could happily spend my time this morning recalling the glories of the past, I believe we must gather that up into the form of a recall to vocation. Those of us who have been lifted up on eagles' wings through our own experience of God's grace and love in Jesus Christ, and through the scriptures which testify to him and have found their way into our hearts and minds, must ask ourselves: what is the task that now lies before us, and what role does scripture play within that task?

There are many reasons why I have a sense of privilege and providence this morning. It is a treat as well as a challenge for me to be able to share in this celebration at all, let alone to share by doing that most central of scriptural tasks, to open the scriptures within a time of worship. But it is a special treat and challenge in that the lectionary readings for this morning, to my delight - because I more or less believe in lectionaries as a way of keeping us obedient to the flow of the text - turn out to include Isaiah 55 and Matthew 13.

I was asked on a radio programme recently which piece of music, if they could supply me with an orchestra, I would like to conduct. A tough one, but I opted for the fifth symphony of Jean Sibelius, not least because of the unique ending, with its six hammer-blows in which everything that has gone before is summed up and celebrated. And today's passage from Isaiah 55 has something of the same quality, not so much hammer-blows but a song of triumph which rises not only from God's people but from the whole creation. This is the climax of the symphony we call Isaiah chapters 40-55: a sustained piece of high poetry of such breathtaking quality that, had it been lost for ever and then dug up by some lucky archaeologist, it would be hailed around the world as one of the greatest pieces of writing of all time.

Isaiah 40-55 expands that great vocational statement of Exodus 19, to a people who had forgotten not only their calling but their identity and their hope. (And let me say that though my task this morning is to paint a large picture on a broad canvas, I haven't forgotten, and Isaiah would not have us forget, that this message is sharply relevant for any here today who have found themselves so battered by life's twists and turns that they, too, find it hard to remember their calling, their identity and their hope. That's how scripture works: the picture is as wide as the world, but every last detail, every last grieving and confused human being, matters vitally within it.)

And Isaiah 40-55 is framed, book-ended if you like, with the magnificent promise not only of rescue for Israel but of God's renewal of the whole created order. The good news of God's rescue for Israel is announced with those memorable words, Comfort ye, comfort ye, my people, but the message isn't just one of comfort; it is the message of God himself coming back to remake not only the fortunes of his people but creation itself. The mountains will be flattened and the valleys filled in to make a highway for God to come back; the grass withereth, the flower fadeth, but the word of our God shall stand for ever. How, in other words, will God restore not only his people but also the whole creation? Isaiah's answer: through his word. That's the opening of the poem. Then, in today's passage, at the very end, we find this theme developed and celebrated: 'as the rain cometh down, and the snow from heaven, and returneth not thither, but watereth the earth, and maketh it bring forth and bud, that it may give seed to the sower, and bread to the eater: So shall my word be that goeth forth out of my mouth: it shall not return unto me void, but it shall accomplish that which I please, and it shall prosper in the thing whereto I sent it.'

Here we have it: the sovereign purposes of God accomplished through his word, the word which does its own work, the word through which God acts not only upon the world, as though from outside, but within the world, like rain or snow irrigating and fertilising the land. And the result is nothing less than the renewal of all creation, with the thorns and briers that had choked both Eden, in Genesis 3, and God's vineyard, in Isaiah 5, replaced now with beautiful trees and shrubs. 'Ye shall go out with joy, and be led forth with peace: the mountains and the hills shall break forth before you into singing, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands. Instead of the thorn shall come up the fir tree, and instead of the brier shall come up the myrtle tree: and it shall be to the Lord for a name, for an everlasting sign that shall not be cut off.' That is the large vision of what God will accomplish through his word: nothing less than new creation, the renewal of the whole created order. From this point there is a line directly to Romans 8, to the liberation of the whole creation from its slavery to decay to share the liberty of the glory of the children of God.

So how does Isaiah's vision, of God's powerful word accomplishing this new creation, actually work? What are the key moves between these two magnificent book-ends? This is a topic for a whole season of sermons, but let me just put down the markers. First, Isaiah's message is about God's kingdom: God becoming king in a new way over all the kingdoms of the earth. God will dethrone the proud and powerful pagan kingdoms, rescuing his people from their grip and his creation from their corruption. That theme reaches its climax in Isaiah 52. But second, Isaiah's message is about God's Servant: the strange royal but then suffering figure who will bear their griefs and carry their sorrows, becoming so disfigured that nobody would ever have believed that he was the arm of the Lord, God coming in person to take the weight of the world's evil upon himself and so exhaust it. That theme reaches its climax in Isaiah 53. But third, if God is setting up his kingdom through the work of his servant, his people are not mere passive recipients of this good news. That isn't how God's word works. God's people are themselves to be grasped by his word, transformed by his word, elevated and ennobled through his word, so that they can be the people of God's new covenant. That comes to its glorious climax in Isaiah 54. And then, as people from every possible background are invited to come in and share this extraordinary new life, the ultimate vision opens before us in Isaiah 55: God's new creation. God's kingdom; God's servant; God's new covenant; God's new creation. I told you this was an extraordinary poem.

And the hidden ingredient all through, and our focus this morning, is God's word. The word, precisely because it is a word and not simply a sword or a sledgehammer, does its work through, and not despite, the lives and minds and imaginations and understanding of God's people. 'Seek ye the Lord,' says the prophet, 'while he may be found'; 'return to the Lord, and he will have mercy, for my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways.' The promise of the re-creating word is part of the invitation to all people everywhere, to you and me this morning, to come afresh to the throne of grace, to turn from sin and injustice and hear God's fresh, and refreshing word, so that we can share in the celebration of new creation, so that we can be people of the fir tree and the myrtle rather than the thorns and the briers. As always in scripture, the vast reaches of God's cosmic purposes dovetail perfectly with the intimacy of God's care for each of his people.

And that is why, at the end of the poem's majestic opening chapter, we find the promise of Exodus translated into a new mode. The people whom God bore on eagles' wings are now invited to fly for themselves. 'They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength: they shall mount up with wings as eagles: they shall run, and not be weary: and they shall walk, and not faint.' This is not just the promise we find in the scriptures; it is the promise that takes effect through the scriptures, as God's people ponder his word, pray over it, and learn the patience of waiting upon him for its fulfilment. The word of God, at work in the people of God, to equip them for the mission of God.

But of course it doesn't stop there. The lectionary can't do everything all at once, and we might equally well have moved this morning into John's gospel, the gospel which the early fathers saw symbolized by the mighty eagle itself, after Matthew's angel, Mark's lion and Luke's ox. It is in John's gospel that we find the Word of God made flesh as the Servant of God, revealing the glory of God so that through death and resurrection he might launch the mission of God, the recreation of the whole creation. Isaiah's themes come rushing together in John's matchless vision of Jesus himself, and as we turn to and fro between them we are indeed deaf if we cannot hear the slow, powerful beating of huge wings, God's eagle carrying us from slavery to freedom and then teaching us to fly in our own right. But the lectionary has taken us elsewhere, somewhere equally important: to Jesus' own announcement of God's kingdom on earth as in heaven, the announcement which takes the form of those strange and wonderful words-in-action that we call the parables. Isaiah promised that God's word would go to work like the rain and the snow, giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater. Now here is the Word incarnate, announcing that the time has come, and explaining God's strange thoughts and ways by telling stories about a sower going out to sow.

Sowing seeds afresh was, indeed, one of the great prophetic images for what would happen when God took his power and reigned after the long years of Israel's exile. The image itself reminds us that God's purposes of salvation are not to rescue people from this world, but to rescue them for this world, to make them his royal priesthood, the people through whom he will deliver creation itself from corruption and death. Once we understand the promise of God's kingdom in the Old Testament, we shouldn't be surprised that Jesus chose to announce it by telling stories about sowers and seeds.

But the stories are just as much warnings as they are promises. Israel can't assume that, when God acts, all his people will have to do is to sit back and enjoy the view. God is indeed establishing his kingdom; but he is doing so in a dramatically unexpected way, a way full of judgment as well as mercy, a way that will be for the fall and rise of many in Israel, a way that will lead his incarnate word to a shameful death. Nobody can presume upon their ancestral inheritance. Just because they're eager for the message, or excited when they first hear it, that doesn't mean that all is well. Much seed will be snatched away by the birds, not now the rescuing eagle but the wild destroyers, or it will remain rootless in stony ground, or be choked by thorns (there are the thorns again, as in Genesis 3, as in Isaiah 55). There is no cheap grace to be had; and we who celebrate our ancestral inheritance of one of the greatest Bible translations of all time are warned, even as we do so, to make sure that our celebrations are not like those who receive the word with joy but have no root, or like those who hear it but allow other things to choke it and prevent it from doing its fresh work in our midst. Indeed, as we are all I'm sure aware, there is always a risk that when we celebrate God's great gifts to us in the past we may forget that the people who gave us those gifts were precisely not the traditionalists but the innovators, the men like William Tyndale who gave their lives to do the unthinkable, who defied culture and tradition to get the message out, as well as the learned and devout men who worked at King James's behest to produce a version that would have the staying power to see off the storms of the seventeenth century and to emerge as the theological and literary backbone of American as well as British society.

The challenge of the parable of the sower is focused on one word, the word which explains what is lacking in the first three soils and what is present in the fourth, the fruitful one. 'When any one heareth the word of the kingdom,' says Jesus, 'and understandeth it not, then cometh the wicked one, and catcheth away that which was sown in his heart.' And then, at the end, 'he that received seed into the good ground is he that heareth the word, and understandeth it; which also beareth fruit, and bringeth forth, some an hundredfold, some sixty, some thirty.' The word, precisely because it is a word, does its work not by bypassing human understanding but by enlivening it. If the word of God is to produce the mission of God it must and will do so through the understanding of the people of God.

And that is why, of course, the project of Bible translation can and must go on, and be joined with the larger project of Bible exposition and teaching, so that new generations and new cultures can themselves grow to maturity, can find themselves in their turn borne aloft on eagles' wings and, through patient and humble waiting upon the Lord, find themselves mounting up with wings like eagles, running and not being weary, walking and not fainting. It is part of the humility that is required of servants of the word that we can none of us predict how the word is going to do this work; God's thoughts remain other than our thoughts.

That is why the supreme task will always be to translate, as faithfully as we can, into the idiom of today and tomorrow, into every nook and cranny of every culture and subculture. We dare not try to squash the word into our own categories or schemes as though we already possessed eagles' wings in our own right. Nor dare we suggest that as long as we have what God provided for yesterday's world and church we don't need to pray for fresh bread for tomorrow. Neither Tyndale himself, nor King James's men, could have imagined or predicted the effect their work would have, including the effect of challenging and correcting some of their own cherished theological and political assumptions. But they would have known, because they were scholars of language, that languages change over time, that words slip and decay and will not stay in place. That is why each generation of Bible scholars and translators and preachers needs to be equipped with that strange but biblical combination of understanding and humility, a humility indeed borne precisely out of understanding, since one of the main things we understand is God's sovereignty and that there is a large gap between his ways and our own.

It is for that combination, therefore, that we should pray today, as we look ahead for another four, or forty, or four hundred years, in the purposes of God, and commit ourselves to being the people who, having been borne aloft on eagles' wings, and brought to himself, will now obey his voice, and keep his covenant, and become, in and for tomorrow's world, a kingdom of priests, a holy nation. And - let us say it once more, as Isaiah would have done, as Jesus would have done - within that large, global, cosmic purpose, the particular concerns that lie heavy upon your heart or mine this morning are not swept aside as trivial. Before Isaiah launches into his glorious picture of God's sovereign grandeur, he pauses to say that 'He shall feed his flock like a shepherd: he shall gather the lambs with his arm, and carry them in his bosom, and shall gently lead those that are with young.' The closing vision in chapter 55, of the word bringing about new creation, does indeed sketch the large picture, but what leads up to it is this: 'Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters.' Somehow, we who serve the word in order to serve our rescuing God and his risen son Jesus need constantly to hold together a vision as wide as creation and a pastoral focus as sharp as the anguish of the person sitting next to us. That, too, is part of our vocation: to be the means, for one another, of bringing about the humble understanding through which the word will produce once more thirtyfold, sixtyfold and a hundredfold; to enable the word of God to do its full work among and within the people of God in order to equip and direct the mission of God; so that they that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength, and mount up with wings as eagles, and run and not be weary, and walk and not faint.

http://www.ntwrightpage.com/sermons/KingJamesAnniversary.htm