An Interview with Matthew Soerens /

An Interview with Matthew Soerens /

Last Friday, President Donald Trump signed an executive order temporarily suspending the refugee program and the issuance of visas for foreign nationals from seven Muslim-majority nations.

The order also put an indefinite hold on all refugees coming from the war-torn country of Syria.

The stated purpose of the policy is to “protect the American people from terrorist attacks by foreign nationals admitted to the United States.” But does the change really make America safer? And what are the other implications for both the church and persecuted Christians from around the globe.

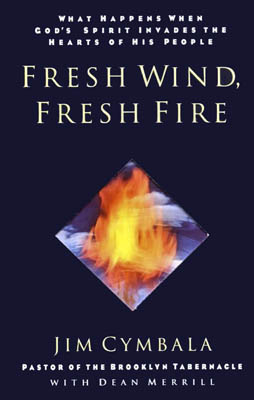

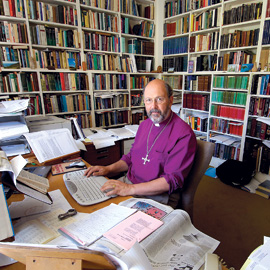

I asked Matthew Soerens, co-author of Seeking Refuge: On the Shores of the Global Refugee Crisis (Moody, 2016) and the U.S. director of church mobilization at World Relief, to discuss how Christians should think about the executive order and issues concerning refugees.

What concerns do you have about the new immigration and refugee policy?

The stated goal of the executive order—to protect the United States from terrorism—is entirely appropriate. In fact, that’s a God-ordained role of government, and we’re glad the president takes that responsibility seriously.

However, I do not believe that the policy changes mandated by the executive order will actually make us safer. I understand people’s fears, but I think that many of them are based on misinformation.

The effects of these policies will be severely felt by some of the most vulnerable people in our world. Many of these individuals have already faced horrific persecution—torture, bombings, even genocide—and to have their hopes of finding safety and a new start in the United States withdrawn is devastating.

How does this order affect World Relief and other refugee resettlement agencies?

After the last of those who were considered “in transit” arrive today, we have no further arrivals of refugees scheduled. We’ve had to tell “Good Neighbor Teams”—the small groups from local churches whom we train and then line up to meet as many arriving refugee families as possible—that we do not know when a family will next be arriving, but probably not for at least four months. We are still ministering to families already here—and still need church partners and volunteers to do so—but there will be far fewer opportunities to minister going forward.

More than 65 percent of our refugee arrival cases are family re-unification cases, so in many of these cancelled cases, our staff have had to break the news to family members here that their relatives who’d had plane tickets purchased are no longer coming—in some cases, at least for a few months, in other cases, such as for Syrians, indefinitely. A colleague in Seattle, who herself came to the United States in 1989 after fleeing religious persecution in Ukraine, had to tell 36 separate families their relatives were not coming. As you can imagine, those are difficult conversations and all the more difficult for those receiving the bad news.

How can we as a nation balance the need for security and compassion?

Our country actually has a remarkable history of both prioritizing the security of American citizens and extending compassion and hospitality to the persecuted and displaced. It became a campaign talking point to say that “we have no idea” who refugees resettled to the United States are, and that we have no ability to vet them, but these are simply untrue.

The reality is that refugees are already subjected to the most thorough vetting of any category of visitor or immigrant to the United States. If a refugee is referred to the U.S. government for possible resettlement—and less than 1 percent of the registered refugees globally ever are—they begin a screening process that usually takes between 18 months and three years to complete. That process is coordinated between the U.S. Departments of State, Homeland Security, and Defense as well as the FBI and National Counterterrorism Center; it includes in-person interviews, biographic and biometric background checks, and a health screening. If there is any doubt of a refugee’s identity or even a hint of concern that they could pose a threat to national security, they are not allowed in.

While any system can be improved, this vetting process has been remarkably effective. Since 1980, when the Refugee Act was signed into law, there have been about 3 million refugees admitted into the United States—and not a single one has taken a single American life in a terrorist attack. A Cato Institute analysis calculates the odds of an American being killed by a refugee-turned-terrorist at 1 in 3.64 billion per year. Do those odds really justify a full shutdown on refugee resettlement from all countries—including countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (the top country of origin for refugees last year) or Burma (the top country in 2015), from which extremist Islamist terrorism is not on anyone’s mind as a significant threat?

Is it wrong for Christians to want to prioritize their persecuted brothers and sisters over refugees of other religions?

As Christians, we’re commanded to love our neighbors—and Jesus’s parable of the Good Samaritan makes explicitly clear that we cannot narrowly define our “neighbor” to include only those who share our faith or ethnicity. Each human being—regardless of religion—is made in the image of God, and all lives are worthy of protection. As such, we are grateful to have had the opportunity to welcome carefully screened refugees of various faiths.

That said, I personally am deeply burdened by the plight of persecuted Christians—and the U.S. refugee resettlement program has been a lifeline for persecuted Christians, more of whom have been allowed into the United States in the past decade than those of any other religion.

While I appreciate the president’s expressed concern for persecuted Christian religious minorities, the actual implementation of this executive order will quite clearly be harmful for Christians as well as Muslims.

Most obviously, the order cuts the total number of refugees for Fiscal Year 2017 to 50,000. Since more than 32,000 have already come in—about 43 percent of whom have been Christians—this order will limit to less than 18,000 those who could possibly come in for the rest of the year. Even if all of them were persecuted Christians—which I believe would be a mistake—there would still be at least 5,700 fewer persecuted Christians allowed in than last year.

Furthermore, though President Trump has spoken of the plight of Syrian Christians, in particular, several lawyers with whom I have consulted agree that the language of the executive order bars all Syrian refugees—including Christians and other religious minorities. Likewise, Iranian refugees are presently barred from entry, most of which over years have been Christians (in fact, less than 5 percent have been Muslims).

My view is that we should prioritize refugees based on vulnerability, as has been the practice of past administrations. In some cases, an individual’s Christian faith makes him or her uniquely vulnerable in a particular context, which is why more than one-third of Iraqi refugees in the past decade and about 70 percent of Burmese refugees have been Christians—far higher in both cases than Christians’ share of the population—because they have been uniquely persecuted for their faith.

By explicitly favoring Christians, it feeds into a narrative that the United States does not value the lives of Muslims, which fuels extremist sentiments and could ultimately put Christians and other religious minorities at greater risk. Open Doors USA president David Curry has warned that the new policy “could tragically result in a backlash against Christians in countries plagued by Islamic extremism.”

Finally, if the United States only resettles persecuted Christians, we are closing the door on one of the most remarkable missional opportunities, as those who are not-yet-Christians, including many from entirely unreached people groups, will no longer be allowed into our country, where local churches have the opportunity—in a context with full religious freedom, where all are free to accept or reject the Christian gospel—to interact with them. From an eternal perspective, do we really think Great Commission opportunity is worth sacrificing for a 1 in 3.6 billion chance of being killed by a terrorist attack?

What advice would you give to pastors who want to faithfully discuss this issue with their congregations?

First, lead with Scripture. If this were not a biblical issue, we’d have no business discussing it in church. But refugees are running throughout the pages, and God has many specific instructions to his people about how to treat vulnerable foreigners. LifeWay Research finds that only 12 percent of evangelical Christians say their views on refugee and immigration issues are primarily influenced by their faith. One tool to address that is the “I Was a Stranger” Challenge, a simple 40-day Bible-reading guide that’s available either in digital form or as a simple bookmark to stick into one’s Bible.

Second, explain the facts. As Ed Stetzer has helpfully observed, facts are our friends. Pastors can help their congregations to find accurate sources for the facts about the security, economic, and demographic dynamics of refugee resettlement.

Finally, whenever possible, I would encourage pastors to provide the space for a refugee testimony—ideally, that of a persecuted brother or sister in Christ or someone who embraced Jesus in the United States after being welcomed by a local church. It is easy to be afraid of huge numbers, but an individual, with his or her own face and testimony, can powerfully melt misconceptions.

My most important encouragement to pastors would be: do not sit this out. At present, LifeWay Research finds that just one in five evangelicals has ever heard a biblical message about refugees or other immigrants. The people whom God has entrusted to your spiritual leadership need a biblical, fact-based view on this topic. If we outsource our discipleship on this topic to talk radio or Facebook, we risk missing out on a divinely orchestrated opportunity both to stand with the persecuted church and also to live out the Great Commission.

https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/what-should-christians-think-about-trumps-refugee-policy