How should one pray? Not even the Psalmists or the disciples knew the answer. The Psalms are filled with pleas for God to place words on the tongues of believers; the disciples were even so bold as to ask Christ to teach them how to pray. The struggle to listen, but also to speak to God, animates the scriptures.

How should one pray? Not even the Psalmists or the disciples knew the answer. The Psalms are filled with pleas for God to place words on the tongues of believers; the disciples were even so bold as to ask Christ to teach them how to pray. The struggle to listen, but also to speak to God, animates the scriptures.

We have inherited the rewards of that struggle—the Psalms and the Lord's Prayer—along with other prayers, from the liturgical life of the church, like the Doxology, and from the life of the community, like the Serenity Prayer. To these inherited prayers we add our own, spontaneous expressions: the whisper of thanks for a car accident anticipated but averted, the silent but specific petition for a promotion or a raise, a team's collective plea to win, the wild screams for understanding after the death of a child.

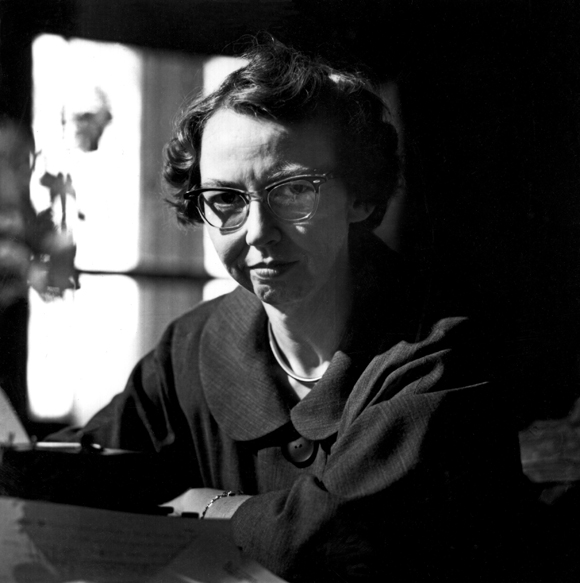

The tension between the conventional prayers that we inherit and the prayers we invent can be fierce, especially for the believer whose vocation is writing. The publication of Flannery O'Connor's "Prayer Journal" (excerpted in the magazine in September) offers a glimpse into one writer's wrestling with the problem of how to pray. William Sessions, who came to know O'Connor when they both wrote for the Archdiocese of Atlanta's newspaper, and who is at work on an authorized biography of her, recently discovered the journal, which records O'Connor's prayer life from January, 1946, through September, 1947, when she was a student at the Iowa Writers' Workshop. Because the first few pages are missing, it begins with an auspicious fragment, "effort at artistry," which it is, not only in its contents but in the life of the one who authored it.

It may seem strange to publish a prayer journal, but believers have long sought encouragement in the prayers of others. While prayers are often private, they always presume an audience, even if it is only the invisible listener, God. There are prayer journals for the young and the old, for particular vocations, for specific seasons in the liturgical year; there are journals crafted from the Church Fathers and Church Mothers, from mystics and martyrs, from the famous and the obscure. Prayers are selected and printed in festive editions for new parents, the sick, the bereaved, the anxious, the environmentally conscious, the imprisoned, the freshly converted, and just about every other group you can imagine.

O'Connor's prayer journal will be of interest not only to those who know her work but to anyone who writes. Her example, of a twenty-year-old terrified of distraction and failure, and bold enough to ask God for success, is inspiring; her sanguine effort to find a way through well-worn territory to original language is instructive. "I do not mean to deny the traditional prayers I have said all my life," she writes in one entry, "but I have been saying them and not feeling them."

"My thanksgiving is never in the form of self sacrifice—a few memorized prayers babbled once over lightly. All this disgusts me in myself," O'Connor laments. A lifelong Catholic, she yearns for a spiritual experience more meaningful than the one her rote prayers provide. The comfort of repetition and the assurance of routine are some of the most immediate benefits of faith, but faith requires something more than cliché.

By writing the journal, O'Connor hoped to rekindle smoldering fires: "My attention is always very fugitive. This way I have it every instant. I can feel a warmth of love heating me when I think & write this to You." The addressee here is God, but already O'Connor is rehearsing her role as speaker, anticipating how she will address a mortal audience. Learning to avoid cliché and speak authentically is a predicament of both prayer and literature, and solving the problem in her prayer life allowed O'Connor to solve the same problem in her fiction.

She sensed that the act of creation in both was not her own. "My dear God," she wrote, "how stupid we people are until You give us something. Even in praying it is You who have to pray in us." Like the Psalmist who asked God for words to pray, O'Connor believed that words themselves are a gift from God. She wrote, "There is a whole sensible world around me that I should be able to turn to Your praise; but I cannot do it. Yet at some insipid moment when I may possibly be thinking of floor wax or pigeon eggs, the opening of a beautiful prayer may come up from my subconscious and lead me to write something exalted."

The same God who provided her words for prayer would also, she hoped, provide her with words for her fiction. "Dear God, tonight it is not disappointing because you have given me a story," she records, contentedly, in one entry. The author of life was also the ghostwriter of her work: "Don't let me ever think, dear God, that I was anything but the instrument for Your story—just like the typewriter was mine."

Amidst thanksgiving, O'Connor was nervous that literary success would distract her from devotion. She intimated the conflict between her faith and her ambitions; the asceticism she desired was at odds with the egotism her work required. "I want so to love God all the way," she wrote. "At the same time I want all the things that seem opposed to it—I want to be a fine writer." The aspiration to acclaim, she knew, was dangerous: "Any success will tend to swell my head—unconsciously even."

The solution, though, was something other than humility—it was the audacity to pray that God would not only give her the words but make those words an instrument of evangelism. "Please let Christian principles permeate my writing," she prayed, "and please let there be enough of my writing (published) for Christian principles to permeate." Her prayers were not only ideological, they were practical, indeed instrumental: "Please help me dear God to be a good writer and to get something else accepted."

She reckoned that her success would be the product of a holy collaboration: "If I ever do get to be a fine writer, it will not be because I am a fine writer but because God has given me credit for a few of the things He kindly wrote for me." Such an understanding of authorship may seem strange, yet for many writers it will echo a sense that their work is somehow foreign to them, that their characters have a life of their own, that there is terrifying mystery in how words arrange themselves on the page.

O'Connor's prayer journal includes mundane occurrences—offending a workshop classmate, reading Kafka, eating too many oatmeal cookies—yet much is missing. There is little mention of Christ or the Holy Spirit; instead, O'Connor prays most often to "dear God." She makes scarce reference to scripture, and mentions only a few theologians. More striking is the absence of family and even friends. There are no prayers for her father, who had died only five years earlier, or her mother, whom she left behind in Milledgeville, Georgia. There are no supplications for the sick or the suffering of the world, which had only recently emerged from the Second World War. These omissions may be the mark of youth, or they may reflect the divisions O'Connor made between this ongoing, private prayer for her vocation and her other, public prayers for the world.

The journal is chiefly an interior one, a record of a Christian who hoped the rightful orientation of her own life would contribute to righting the orientation of the world. O'Connor yearns for prayer to come effortlessly, even while exerting great intellectual effort to understand and induce it. "Prayer should be composed I understand of adoration, contrition, thanksgiving, and supplication and I would like to see what I can do with each without an exegesis." Confessing that her mind "is a prey to all sorts of intellectual quackery," she asks for a faith motivated by love, not fear: "Give me the grace, dear God, to adore You, for even this I cannot do for myself."

The journal reflects a single year in the life of a believer—it includes just under fifty pages of prayers from a lifetime filled with them. It is the attempt of a young writer to reconcile her worldly ambitions with her heavenly understanding. The task she set for herself, to invigorate her dulling faith, was accomplished by the deliberate, contemplative practice of praying in her own words. By refashioning the prayers she inherited and practiced every day at Mass, O'Connor was able to find new language for belief.

This coincided with her finding her own voice for fiction. By September of 1947, when the journal ends, she was at work on her first novel, "Wise Blood," which would be published in 1952. Not only did O'Connor find a way of making her writing into a religious practice, a ritualized, disciplined act that was itself spiritual, she also achieved the level of success she prayed for with such equanimity: she published two novels and wrote thirty-one stories that appeared in numerous literary journals, and, decades later, her work remains a staple of fiction anthologies and university syllabi. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that she is the most important Catholic author in American letters.

But a successful literary career was not her only prayer, and one of the most plaintive sections of the entire journal is devoted to suffering: "Looking back I have suffered, not my share, but enough to call it that but there's a terrific balance due." O'Connor wrote these words only a few years before she experienced the pain that was initially mistaken for rheumatoid arthritis. Later, it was correctly diagnosed as lupus, the disease that killed her father, and that would eventually kill her when she was only thirty-nine years old.

What she accomplished in the interim, through the debilitating pain of her disease, is miraculous. Luck is a more comfortable word for our age, but I believe she would have used the word "miracle" to describe her career. For so long, O'Connor's faith could only be guessed at from her letters, the few lectures she gave, and essays she wrote explicitly addressing religion, notably "The Catholic Novelist in the Protestant South" and "The Church and the Fiction Writer." Now we have a small but significant record of what she believed. It is a gift to anyone who desires to understand O'Connor's work, and to anyone who seeks to understand writing as a religious calling.

For years, when I was starting to write, I prayed, "God, let my words lead them to yours; let me lead them to you." I wrote that prayer in the margins of pages and on the inside covers of my notebooks, hoping that I would produce something that might serve the Lord. Unlike O'Connor, I had no idea how that might happen or the way it all might work, but, like her, I kept praying.

Reading her journal, I laughed, thinking that I should have been a lot more specific in my demands and humbled by the sophistication of her desire to integrate her piety with her profession. Her prayer journal ended when her prayers became fully integrated in her writing; the literature itself was a prayer, an offering to God.

O'Connor found the same way through cliché to invention in her spirituality and in her writing. How else could the tired old stories of tenant farmers, street prophets, ne'er-do-well teen-agers, agrarian widows, travelling bible salesmen, and murderous misfits become such celebrated works of fiction? Every believer finds a way to speak to God, but O'Connor also found a way to speak to everyone else.

Casey N. Cep is a writer from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. You can follow her on Twitter @cncep.