Many voices are encouraging you and me to get involved in America's "race conversation." It's the right encouragement, but, goodness, it's tough.

Many voices are encouraging you and me to get involved in America's "race conversation." It's the right encouragement, but, goodness, it's tough.

As a church elder, I have joyfully watched my own congregation that meets on Capitol Hill in Washington grow increasingly multi-ethnic in the last few years. But there's a brand of growing pains a church feels as its members learn to love one another when they have little in common but Christ.

Since the Zimmerman verdict several weeks ago, I've heard from church members first on this side, then on that side; to those outraged and to those sympathetic with the verdict; to white concerns about crime statistics and then black concerns about profiling; back and forth, back and forth, back and forth.

No, not all blacks or whites (or Asians or Hispanics) fall so cleanly this way or that. But those are the two broad camps, and I've worked hard at listening to both sides. The downside is that both my head and heart have felt like a tennis ball, swatted back and forth. One day I'm convinced of this; the next I'm convinced of that.

My big conclusion through it all? I'm not sufficient for these things!

The conversation befuddles me. That's not postmodern modesty. I'm genuinely uncertain about the right political, moral, and cultural explanations. Who's at fault and where? Who needs to do what? There are lots of answers. It's complicated. You'll need to go to wiser heads than mine for solutions.

But I do have a few observations about the conversation. Take them as the perspective of one white guy who has watched (and felt) this tennis match.

1. Private conversations across ethnic lines are essential to making progress.

Talking with members of your own ethnicity can be helpful, but they can also reinforce our own little cycles of insular logic. When you take the awkward and scary step of explaining yourself to those of a different ethnicity, and when you really listen to their perspective, you discover your logic isn't as foolproof or clever as you thought it was.

2. It's easy to forget what Jesus said about specks and logs.

Jesus, remember, told us to take the log out of our own eye before taking the specks out of others'. But I think former NBA star Charles Barkley was basically right when he said our country never discusses race "until something bad happens, and when we do, everyone protects their own tribe."

Or let me put this point a little more sharply. Both sides have their unique blindnesses and idols they're trying to protect. Yes, I'm indicted, too. In fact, I believe partiality to our own ethnicity is universal, and such partiality is a hair's breadth away from the outright malice of racism.

Why are we so partial? The "old man" in each of us remains idolatrous, and the heart of idolatry is an inordinate love of self, which in turn means we prefer people who look like we do. But praise God for the "new man," right? Little by little the old man is put to death. Still, the saints remain mixed, all of which means it's hard to enter the conversation if you're not ready to learn and maybe even to repent.

3. Both sides are looking for understanding and sympathy.

Black people want white people to understand the injustice of being profiled. White people want to be understood as "not racist." I think understanding should extend both ways. By analogy, Scripture tells us in one breath to not pervert justice for the poor or to show partiality to the poor (Exod. 23:2, 6). You need to listen to those who've been disadvantaged, but that doesn't mean you stop listening to those who've had the advantages. The advantages and disadvantages in the race conversation are real, just like poverty is real. But both sides have something to say, and both have some listening to do.

4. The conversation is difficult because it moves back and forth between our identity as individuals and as group members.

In one moment, blacks and whites alike will say, "Hey, I'm an individual. Don't assume that just because I'm black/white. . . ." Then, in the next moment, we'll defend our group. Thing is, both perspectives are legitimate for their part. We are individuals, but our group memberships dramatically affect our individuality—our sense of self. It's not enough to say, "We just have to treat everyone as individuals," because different groups experience things differently. But it's certainly not correct to treat people simply as members of their group.

5. The conversation is difficult because there are facts, and there are interpretations of facts, and both are important.

I once heard the following story in a sermon: A man was sitting in a train car with his crying infant. The crying continued for some time until another man, sitting across from the man with the infant, finally scolded, "Would you give that child to its mother!?" The first man replied, "I would, but she's in a coffin in the back of this train. We're traveling home to bury her." The second man, with a changed heart, then offered to take a turn holding the crying infant. There are facts: the crying infant. And there's a larger context that affects how we interpret those facts: the infant is crying for his newly dead mother.

In this race conversation, different people pay attention to different sets of facts because they have different interpretations about the significance of those facts ("It's all about the crime statistics" or "It's all about discriminatory laws" or "It's all about family breakdown" or "It's all about enforced cycles of poverty over a generation").

6. We will not be able to understand everything we want to understand.

It's natural to search for the broad, objective perspective; for the tidy way to explain everything. But this conversation, more than most others, has left me befuddled, humbled, and praying. Not a bad place to be, I suppose.

Sometimes I grasp the perspectives of my black brothers and sisters. Other times, I just can't. I try, but I cannot enter all the way into their shoes. It's analogous to how I can feel with my wife. My experience is not hers. We need to continue seeking shared ethnic understanding—political, spiritual, moral, cultural—just like I must seek to live with my wife in an understanding way. But this topic requires vast measures of humility. Generations of accumulated sin and sinful responses to sin make it difficult to see clearly.

Thankfully, the inability to understand other people's perspectives provides the opportunity to learn the posture of dependence and trust toward those who are different than us. Autonomous Americans won't like the sound of that, but it's a biblical way to live (e.g. 1 Cor. 12).

7. The "fix" just might be found more through relationships than through discussions about race.

Yes, that's a false dichotomy, because relationships are built through discussions. I only mean that I've seen a white Christian brother and a black Christian brother discuss their perspectives and not fully agree by the conversation's end. But both were sincere, careful, and patient in the conversation, and the shared experience of working through it taught them to trust one another more. They laughed together and grew in love, which covers a multitude of sins. They didn't understand one another's thinking, but they better understood one another as people.

Likewise, spending time with my friends of different ethnicities grows my love for them, and they for me (I think!). And the more time we spend together having meals, enjoying holidays, reading the Bible, talking about our kids, comparing marriage notes, and living life generally, the more our history is a common one. The more our perspective on life is a shared one. And little by little, I think, we grow beyond the divide.

8. Maturity makes a huge difference in this conversation.

Turn to the book of Proverbs to see what I mean by mature. Mature people are quick to listen and slow to speak. Mature people assume the best in the other person. Mature people recognize the wisdom of multiple counselors, and so forth. I'm slightly reluctant to encourage people who lack this maturity to have private conversations, because more harm than good might be done. There are times to keep the mouth closed, and Proverbs will tell you the more immature and foolish you are, the more often you live in such times.

9. The solution is most certainly in the gospel.

Our created humanness, no matter the skin color, is "good" (Gen. 1:31). But neither our skin color, nor our family name, nor our nationality, nor anything else gives us standing before God. Our worth, our value, our justification, our boast depends on none of these, nor in anything intrinsic to us. Neither the color of your skin nor the name of your momma gives you admittance to his throne room. The work of Christ alone does.

And so it is with everyone else standing in his throne room. They aren't there because they're black or white, rich or poor, righteous or racist. Everyone stands by grace alone.

Are you partial to your own group? I am. But that's only because I'm foolish enough to rank people by standards the all-wise God of creation does not.

Imagine for a second what it might look like to fully recognize that we stand before God utterly by grace—I mean, really, truly, totally as a freebie—when wrath is in fact deserved. Would you and I still show preference to persons who share our skin color?

10. Christians should not simply read from the culture's favorite scripts.

I assume both the liberal and the conservative talking heads say true things from which we can learn. But shouldn't the regenerate people of God who trust in the worthiness of Christ alone sound different than either? Shouldn't we be reading from a different script—one our non-Christian friends find perplexing because sometimes our sympathies are here, sometimes there?

Peter calls black, white, Asian, Hispanic Christians together a "chosen race" (1 Pet. 2:9). Does this reality affect the look and feel of your church? Does it affect how you feel about yourself when you wake up in the morning?

Insofar as both the political left and right seek solutions in something other than the vicarious righteousness and worthiness of Christ, they operate according to a different paradigm. Ironically, by insisting our worth and standing depends on our "race" and skin color, they reify our divisions. They make me feel good about myself "because I'm white" or "because I'm black," which means the temptation to partiality toward my own kind will forever remain.

In the church alone can we simultaneously affirm these two points:

God created people as both different and good.

Those differences hold absolutely no weight in our standing or rank relative to one another, since our worthiness depends on something outside of us—on the worthiness of Christ.

11. If the local church cannot grow toward unity in diversity, forget about America.

We are the regenerate people of God. We are the new creation. The world may persecute or privilege us according to its categories, and those persecutions and privileges are existentially significant. We should mourn and rejoice with one another as we stumble in together on Sunday morning, worn out from a week of battling the world's powers and ideologies. But those categories are never ultimate (see Gal. 3:28). We live in them, but we're not of them.

That means each of us needs to stand before Jesus and say, "You've created me as male. How would you have me steward my maleness?" Or, "You've made me a black. How can I use my blackness for your glory and the good of the church?"

Here in the local church, more than anywhere else on the planet, is where Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream of little black boys and girls sitting down with little white boys and girls should be realized. Christians, turn first to your churches. What can you do to lift up and love members of different ethnicities in your own congregation? Here's an idea.

12. Let's outdo one another in showing honor, as Paul puts it (Rom. 12:10).

How can the majority outdo the minority in showing honor, and how can the minority do likewise? Or do you think one of them is absolved from this command?

How can you personally—in practical ways—outdo members of other ethnic groups in your church in showing them honor? Take a minute to think about it. Right now. What can you do?

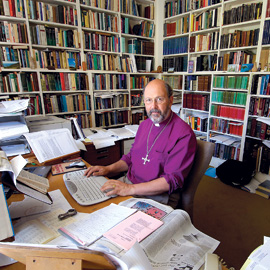

Jonathan Leeman is a member of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., editorial director of 9Marks, and author of The Church and the Surprising Offense of God's Love, Reverberation, Church Membership, and Church Discipline. His PhD work is in the area of political theology. You can follow him on Twitter.

http://thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/tgc/2013/08/09/12-lessons-from-the-race-conversation/